What makes a good city? You need the right codes

Second in a series of illustrated essays: Part 2: How to make Charlotte a better city

In the first illustrated essay in this series, I explained the importance of urban design in the process of improving our city and laid out six basic strategies that guide high quality and sustainable design and planning practice.

The essay also illustrated some typical design blunders – using South End as a case study where poor architectural and urban design has diminished the quality and safety of the public streets and other spaces along and around the light rail line. Furthermore, these poor designs from the private sector have undercut the public investment of taxpayer dollars that funded the catalytic transit infrastructure.

How can we stop these design and planning mistakes from damaging our city? The bad examples we endure daily were designed by licensed architects and given the green light by qualified planners. Clearly we can’t rely on individual talent to always produce good results. Like any other city, there are excellent professionals among the architects and planners here in Charlotte. There are also some developers who take seriously their job of building bits of our city. But if 45 years in design practice and education has taught me anything, it’s that a wide range of abilities exists within the professions that plan, design and build our urban environment. Sadly, a surprising number of folks in these groups fail to understand the principles of good urbanism and how everyone benefits from good urban design.

To download the illustrated essay, click image

To download the illustrated essay, click image

.

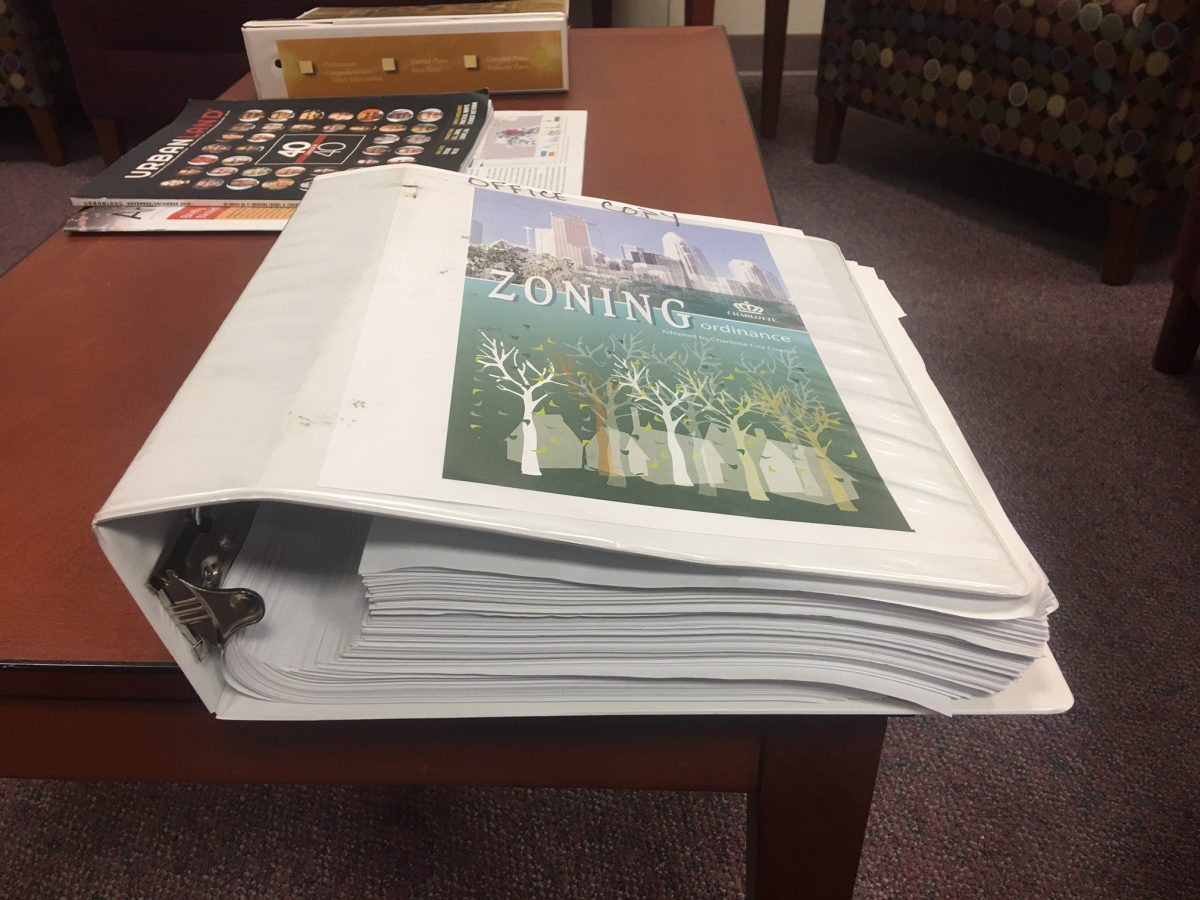

The key to getting a consistently good quality of urbanism for our city relies not on individual talent that may vary from good to bad, but rather on the book of urban regulations we call a zoning code. And people who pay attention to such things admit Charlotte’s zoning code is woefully unfit for this purpose. Most of them also know Charlotte is undertaking a major, multiyear endeavor to rewrite the zoning code into what’s called a Unified Development Ordinance (UDO). As the name suggests, this ordinance aims to incorporate improved planning and urban design concepts while smoothing out irregularities and discrepancies between the city’s multitude of separate ordinances, which today are full of confusing details that sometimes contradict each other.

Charlotte’s current zoning ordinance, a printed version of which is shown above, is complicated, hard to follow, contradicts other city ordinances and, a consultant told the city in 2013, often doesn’t produce the development that city plans call for. Photo: Mary Newsom

Charlotte’s current zoning ordinance, a printed version of which is shown above, is complicated, hard to follow, contradicts other city ordinances and, a consultant told the city in 2013, often doesn’t produce the development that city plans call for. Photo: Mary Newsom

If done correctly, this UDO could chart a sustainable and prosperous future. Or it could be riddled with compromises that perpetuate the “pot-luck” urbanism we now have, where one project may be great while others nearby are awful.

At the outset, this UDO must state clearly the city’s vision for its future. The contents will provide the directions required to reach that objective. But without a well-articulated vision – low on platitudes and generalities and high on specifics – the UDO becomes directionless, a bunch of good ideas going nowhere.

The easiest metaphor to understand the UDO and how it works is to think of it as a cookbook with a theme. Say for example, we want to write a cookbook about “meals for healthy living” to promote a healthy lifestyle. The book would be full of ideas, examples and instructions about how to achieve that goal. It would contain a collection of well-tested recipes focused on the theme, and each main dish recipe would list the appropriate ingredients, detailing quantities and directions. We would then likely be referred to other pages for side dishes, sauces, etc., that coordinate with and complement the main dish.

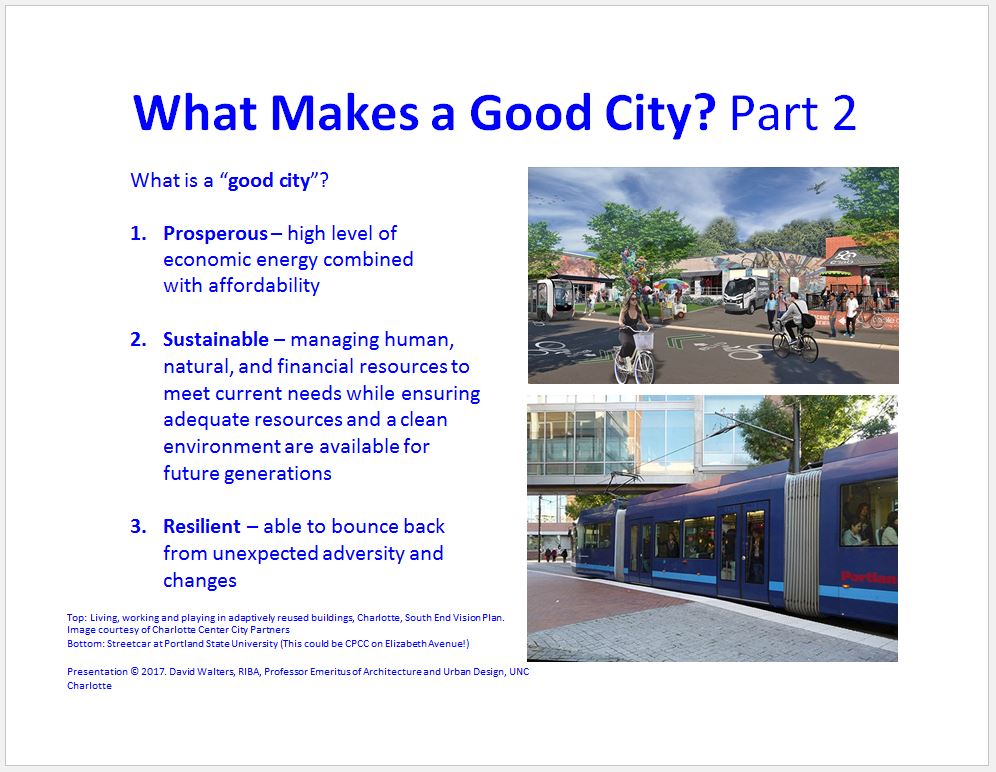

Similarly, Charlotte’s “UDO for a Prosperous, Sustainable and Resilient City” (our urban cookbook title) would define the urban objectives for our city and provide coordinated sets of “recipes” for making a menu of prosperous, attractive, safe, and sustainable urban places.

[highlight]A good UDO can produce an attractive, sustainable, equitable and prosperous city from designers, developers and planners of varying degrees of expertise.[/highlight]

Few cooks would have a problem using a cookbook or understanding its themes and contents, and a good UDO keeps those same straightforward organizing principles. It states the premise of the book, organizes its “urban recipes,” and cross-references relevant additional material. My hypothetical examples in the visuals that accompany this essay must not be confused with actual proposals for Charlotte’s future UDO. These limited examples are taken from codes in other communities I’ve been involved with, and I’ve simplified the level of detail for easier comprehension.

Each of those sample pieces of a hypothetical code deals with some critical component of good city-making and provides architects, planners, developers, engineers, elected officials and citizens with illustrated and easily digestible rules and regulations. Using my cookbook metaphor, the “urban recipe” might be for, say, a “Mixed-use Neighborhood Center” – a specific type of place (a “place type” in our evolving jargon) that the city and/or property owners want to develop or reinforce in certain locations. The cluster of buildings and mixture of uses along a stretch of Selwyn Avenue in Charlotte provides a useful illustration of a mixed-use neighborhood center development.

The Selwyn Corners and Tranquil Court developments along Selwyn Avenue at Colony Road and Tranquil Avenue in Myers Park is an example of a mixed-use neighborhood center, with developments offering multifamily and retail, with parking hidden from the front sidewalk view. Photo: David Walters

The Selwyn Corners and Tranquil Court developments along Selwyn Avenue at Colony Road and Tranquil Avenue in Myers Park is an example of a mixed-use neighborhood center, with developments offering multifamily and retail, with parking hidden from the front sidewalk view. Photo: David Walters

As with any “main dish,” complementary “side dishes” would complete the meal. In urban zoning terms, those would be things such as rules for street cross-sections, how parking must be configured, landscaping and open space design etc.

Just as good cookbooks can produce tasty results from cooks of all abilities, so a good UDO can produce an attractive, sustainable, equitable and prosperous city from designers, developers and planners of all stripes.

But one, clear word of warning: For best results, follow the recipe!

David Walters is professor emeritus of architecture and urban design at UNC Charlotte. He presented a version of this to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission at its retreat Sept. 14.

Opinions in this article are those of the author and may or may not reflect the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

TO READ PART 1 IN THE SERIES OF ILLUSTRATED ESSAYS, CLICK IMAGE.

To read Part 1 and find a link to the illustrated essay, click image above

To read Part 1 and find a link to the illustrated essay, click image above