What makes a good city? Urban design, explained

First in a series of illustrated essays: Part 1: An introduction to urban design

“Why do the apartment buildings all look the same?”

“Why does South End look so boring?”

“Why is it so dense?”

“What about traffic?”

Questions like these have become common in Charlotte over the past several years. Charlotte neighborhoods such as Plaza Midwood, South End, Elizabeth and uptown have seen substantial redevelopment, and the quality of those projects has varied from very good to abysmal. Elected officials are tasked with approving or denying these projects, and to many observers, some decisions by the council and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission seem hard to understand.

I have sympathy for those appointed and elected officials. They are bombarded with conflicting opinions, hyped-up images from developers, real-estate jargon, and innumerable empty platitudes about “community, ” all while facing real community opposition to almost everything, and whether a good or a bad project makes little difference.

Amid this confusion, bias and hypocrisy, our appointed and elected officials are expected to distinguish objectively between good projects and bad ones. They should resist community opposition when it’s misplaced and withstand developers’ pressure to bend (or break) city policies so those developers can make more money. Elected officials are also supposed to ignore the large amounts of money developers contribute to their “war chests” for their campaigns. Within this maelstrom of conflict, our elected officials hold the ultimate power to grant or withhold legal rights on property. Their decisions alter the city’s landscape for decades – for better or worse.

To download the illustrated essay, click the image above

To download the illustrated essay, click the image above

At the same time, residents and voters navigate this maze with a similar lack of specialized knowledge and tend to complain reflexively about the same topics – density and traffic – whether they are relevant or not. We all need to become better educated on these topics. For instance, with an open mind we can learn that sometimes density is the solution, not the problem, and that congestion can be a sign of an attractive and successful part of town.

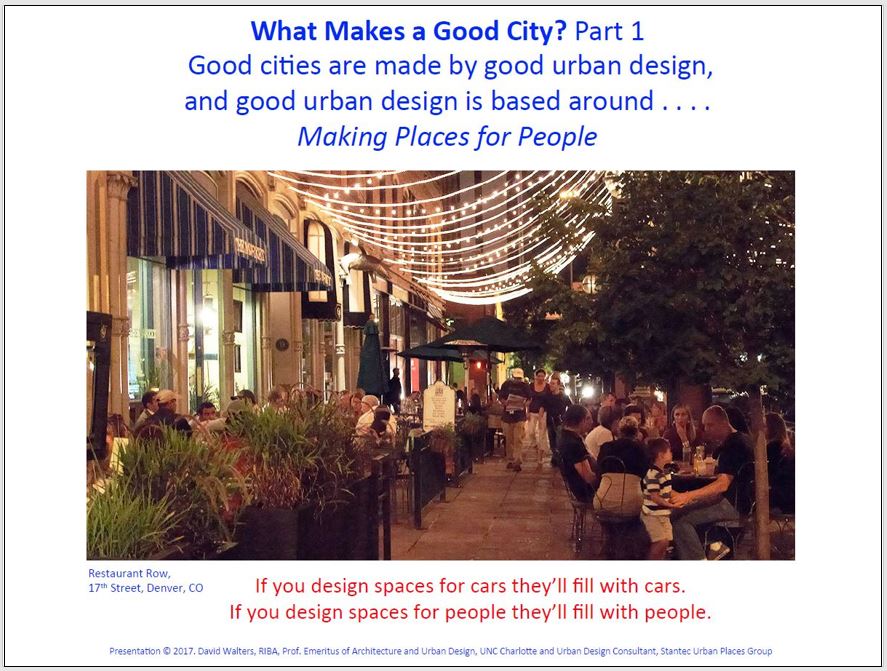

At the heart of this debate is the practice of urban design, a special expertise that’s a trifecta of architecture, planning, and landscape design. Simply put, urban design is the discipline that plans the public spaces of the city to make sure they’re attractive, safe, and efficient. And “public spaces” does not mean only parks, plazas and playgrounds. Streets and alleys are also public spaces. So are squares, traffic circles and greenways. Urban design embraces issues of transportation, including on foot, by bike and in cars, buses, trams and trains. It orchestrates the special character of a neighborhood or district and sorts out how that part of a city relates and connects to the other parts.

At the farmers market in downtown Des Moines, Iowa, the building facades lining the streets act as “walls” to the linear “urban room” holding all this activity. How those facades are designed helps define whether the space is attractive and functional – or not. Photo: David Walters

At the farmers market in downtown Des Moines, Iowa, the building facades lining the streets act as “walls” to the linear “urban room” holding all this activity. How those facades are designed helps define whether the space is attractive and functional – or not. Photo: David Walters

In short, urban design shapes our “public realm,” the spaces we all share, places that are public with open access. These are the “urban rooms” in which we live our public lives. Buildings are the “walls” that shape, enclose, and define these urban rooms.

This preface, with the illustrated slideshow accompanying it, is the introduction to a series of illustrated essays intended to provide resources for elected officials, government staffers and regular residents. The series forms a simple primer about urban design that can make everyone who cares about Charlotte more informed – and thus more able to make good decisions.

Six strategies essential for successful urban design

1. Block size and block structure must be scaled for easy pedestrian use.

2. Streets must connect for efficient travel choices. This means small block sizes.

3. Fronts must be distinct from backs. (Fronts face fronts, and backs face backs.)

4. The relationship between public realms and private realms should be carefully designed.

5. Density is essential in key locations: You can’t have active public spaces without it.

6. Mixing uses in walkable proximity promotes economic and physical sustainability.

David Walters is professor emeritus of architecture and urban design at UNC Charlotte. He presented a version of this to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission at its retreat Sept. 14.