Work of ‘hidden profession’ is all around you

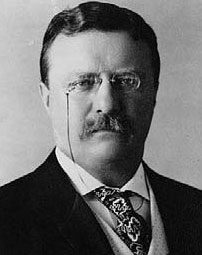

The year was 1908. President Theodore Roosevelt, nearing the end of his second term, convened a Governors’ Conference at the White House with the primary goal to formulate a national philosophy of conservation based on efficient use of finite resources and scientific management of renewable ones.

According to Edmund Morris’ Theodore Rex, the invitation list included governors of the 45 states and territories that made up the United States, Cabinet secretaries, all nine Supreme Court justices, members of Congress; representatives of 68 professional societies (among them civil engineering, architecture and historic preservation). But of the 360 invited guests, there was not one planner.

T his was no snub. The planning profession did not yet exist. According to the American Planning Association (APA), the origin of planning as a professional movement can be traced to the 1909 “National Conference on City Planning” in Washington.

his was no snub. The planning profession did not yet exist. According to the American Planning Association (APA), the origin of planning as a professional movement can be traced to the 1909 “National Conference on City Planning” in Washington.

Fast forward 100 years. By 2010 the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics counted more than 40,000 planning professionals in the nation, with a similar number affiliated with APA as members – including some 1,400 members of the N.C. Chapter of APA (APA-NC).

My own introduction to planning came in a high school social studies career class in 1976. After getting a master’s degree in city and regional planning, I’ve worked for more than 25 years as a professional planner at the local level – in communities from New England to North Carolina – from a historic village to a booming metropolitan suburb. I have been involved in virtually every aspect of planning, from land use and transportation to historic preservation and economic development.

I have seen first-hand the value of planning and its impact on the quality of life in communities both small and large. But due in part to the nature of planning work – it’s long-term, behind the scenes and largely apolitical – the public’s understanding and recognition of planning is low. If I tell someone I am a “planner,” without qualifying that title with “city” or “transportation,” I am often met with a blank stare, with the person asking me what I do for work!

Planning – what I call the “hidden profession” – may well be one of the most important professions that the public doesn’t know exists. While the positive impact of planning and planners on our built and natural environments are clearly visible, the public is not typically aware of those impacts, since most planners do not (a la Picasso) “sign” their work.

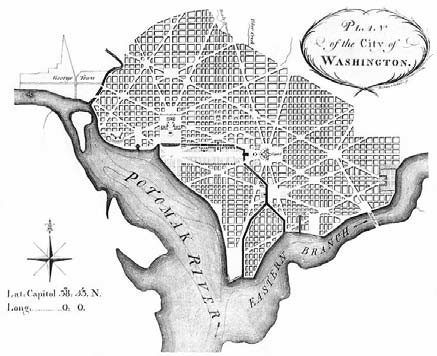

For several years I’ve taken part in a career day at a local high school. In trying to explain to students what planners do, I typically begin saying this: “Behind every great city is a great plan.” I show images of the Parthenon in Athens; the Champs-Élysées in Paris and the National Mall in Washington. I begin to get some nods of understanding and a greater appreciation for “who” is behind some of the world’s great places and iconic destinations.

Great places (and plans) don’t just happen – someone (whether it’s Baron Haussmann in Paris or Pierre Charles L’Enfant in Washington) is responsible for their development and implementation.

North Carolina has many examples of great plans (and planners) that have helped create places North Carolinians know and love. The APA-NC’s “Great Places in North Carolina – Great Main Streets” contest highlights some of the great planning in communities as diverse as Edenton, Raleigh, Davidson, Mount Airy and Asheville. (See “Concord and Davidson Main Streets named ‘Great Places’ in state competition”)

Since moving to North Carolina in 2005, I have been involved in a number of progressive land use, transportation, economic development and natural resource planning efforts at the local, regional and state level. The high caliber of planning in North Carolina is evident in the many cities and towns here that continue to attract new residents at a rapid pace, in large part due to the high quality of life that results from good planning and its effect on the built and natural environments.

Great plans are:

- Visionary. They focus on the big picture.

- Comprehensive. They are multi-faceted in scope and approach.

- Strategic. They are purposeful in application and implementation.

- Progressive. They address complex issues through innovative solutions.

What do planners offer the communities where they work?

- A comprehensive understanding of the natural and built environments.

- The ability to develop consensus and a shared vision for growth and development.

- The skill and expertise to implement plans and policies consistent with a community’s vision.

As I look ahead to the rest of my planning career, I’m excited and enthusiastic, buoyed by confidence in the value of planning and its positive impact on our communities.

While our work may not always receive acclaim, we planners know it is important and necessary. And we know this, too: If Teddy Roosevelt were sending out his 1908 invitation in 2013, we’re confident planners would be on the guest list.

Views expressed in commentary articles here do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.