The mystery of trail trees

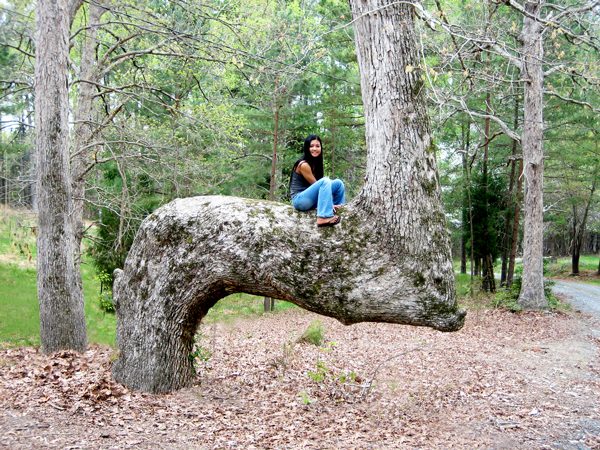

Years ago, a friend in Uwharrie showed me a crooked tree on his family’s property. Its trunk was bent at two right angles, creating a horizontal span about 4 feet off the ground. He said they called it their “ducker-header” tree. Their clever terminology came to mind again recently when I learned about the Trail Tree Project, an effort spearheaded by a group called the Mountain Stewards. Members believe these trees are a legacy of the American Indian presence in our region.

American Indians in the West often painted or etched rocks with symbols – what we now call pictographs and petroglyphs – to mark trails, water sources and other significant places. Tribes in the Southeast would have likely done the same with the materials at their disposal, namely trees. For the most common type of bent tree, it seems a sapling was bent horizontal against a yoke stick, then tied into position with a rope of animal hide. Further manipulations might have been needed – a cut on the outer side of the trunk to relieve tension on the wood and the removal of vertical limbs that sprouted from the trunk.

Some naysayers claim the American Indians weren’t intelligent or sophisticated enough to employ these techniques. Still others wonder why this practice wasn’t described in detail by early explorers or why there’s a lack of common knowledge among tribal elders today. In Mystery of the Trees, authors Don and Diane Wells say the Indians were probably reluctant to share this information since they didn’t trust white settlers. They also remind us of the forces that might have lead to the loss of this knowledge. Tribal populations were decimated by diseases brought to the New World from Europe. Those who survived were persecuted and relocated. They were also “civilized” and forced to adopt the ways of white culture. Their entire society was upended within a few generations. In the midst of this upheaval, the details of using trees as markers must have seemed irrelevant.

I’ll confess I come to this hypothesis with some skepticism. We humans tend to see ourselves as the center of the universe – the term for this is anthropocentrism – and I wondered if this might lead us to attribute these contorted trees to the work of human hands instead of giving Mother Nature the credit. Wells admits that natural forces could be responsible for shaping trees in a similar fashion, but he points out they reject the vast majority of trees brought to their attention. The trees they accept must be old enough to have been manipulated during the period when Native Americans were known to live in the area. In general, a tree must be greater than 20 inches in diameter unless there are other artifacts in the immediate vicinity.

I’ll confess I come to this hypothesis with some skepticism. We humans tend to see ourselves as the center of the universe – the term for this is anthropocentrism – and I wondered if this might lead us to attribute these contorted trees to the work of human hands instead of giving Mother Nature the credit. Wells admits that natural forces could be responsible for shaping trees in a similar fashion, but he points out they reject the vast majority of trees brought to their attention. The trees they accept must be old enough to have been manipulated during the period when Native Americans were known to live in the area. In general, a tree must be greater than 20 inches in diameter unless there are other artifacts in the immediate vicinity.

To date, they have documented more than 2,000 trees. In the Southeast, most of these trees have been white oak. Given an average lifespan of 300 years – and the ability to sometimes live twice as long – a mature white oak in our region could have been manipulated around the time John Lawson encountered native settlements in the Uwharries during his expedition through the Piedmont in 1701. Even though our forests have been logged multiple times since Lawson’s visit, crooked trees are often spared since they’re of little value. In the mid-1800s, Dr. Francis Kron wrote that old-timers still recalled American Indians passing through the area around Morrow Mountain. Perhaps they manipulated trees to mark important sources of rhyolite they prized for making arrowheads. Two bent trees stand near the cabins at Morrow Mountain State Park, but Ranger Ron Anundson isn’t sure they’re old enough to coincide with an indigenous presence in the region.

I recently went to revisit my friend’s ducker-header tree in Uwharrie. As I had hoped, it was in fact a white oak, and it was even larger than I remembered. The diameter at breast height – or as close as I could get before the trunk flared and curved – was 37.3 inches. The horizontal trunk was an inch larger. A white oak that size has to be old, especially one growing on a rocky hillside. Just for fun, I pulled out my compass to check the orientation. When it pointed due north, a chill ran up my spine. My friend said another tree farther up the hill pointed in roughly the same direction, and a similar tree at the foot of the hill had died years ago and fallen into the pond. Perhaps these trees had pointed to that water source. I closed my eyes and tried to picture what significant landmark might lie in that direction. I later consulted a map and found it aligned with the Uwharrie River. I embraced the possibility of hunters funneling up the valley, returning to the Keyauwee village where John Lawson had stayed for three days on the banks of Caraway Creek.

So is this tree the work of man or nature? Perhaps this is a case where irrefutable proof is overrated. Both are capable of wondrous things. These mysterious trees might not guide us to sources of stone or water, but if they inspire us to reflect on our natural and cultural history, they’re still significant markers.

To see photos of trail trees, and to submit your own, go to http://www.mountainstewards.org/project/internal_index.html