An (un)conventional, but globalizing Charlotte

UNC Charlotte’s Heather Smith, associate professor of geography, researches restructuring cities, immigrant settlement and adjustment, and the causes and implications of Hispanic “hyper-growth” in Charlotte and the South. She spoke recently with UNC Charlotte Urban Institute graduate student Josh McCann. Her remarks, edited for brevity and clarity:

Q. You’ve said before that Charlotte is not yet a global city but rather a globalizing city. What’s the difference?

A. Global cities are cities that have been commonly identified as leading cities across the international landscape … centers of knowledge, information, capital, control. They are gateway cities for migrants of all shapes and colors. They meet a certain set of criteria: Driven by a service-based economy, having social and economic polarization, being a gateway, the number of headquarters, flights to international destinations, the depth and density of links with other cities, how much control corporations within the city have over particular components of the global economy, how many shipping lanes, things like that. The pace of change in a global city is incredibly rapid.

A. Global cities are cities that have been commonly identified as leading cities across the international landscape … centers of knowledge, information, capital, control. They are gateway cities for migrants of all shapes and colors. They meet a certain set of criteria: Driven by a service-based economy, having social and economic polarization, being a gateway, the number of headquarters, flights to international destinations, the depth and density of links with other cities, how much control corporations within the city have over particular components of the global economy, how many shipping lanes, things like that. The pace of change in a global city is incredibly rapid.

There are primary, secondary, tertiary global cities all the way to a fifth and sixth level and beyond. Cities like London, New York, Tokyo are primary global cities, commonly and widely recognized as at the very top.

A globalizing city has some of those markers but is still on an upward trajectory of connecting into both the global economy and also broader processes of globalization. Charlotte – even though it is not on the radar of many global city scholars – is around the fifth or sixth (level), largely tied to the bank headquarters here. It is not yet fully realized as a global city. Three things really pop out for me:

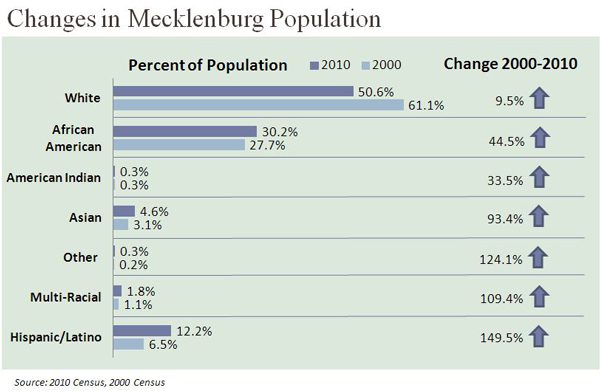

- One is the process of internationalization. We are on the national radar as a city that is leading in rates of growth of the foreign-born, particularly Hispanic-Latino populations, but it’s not just that population.

- Second would be social and spatial polarization. When you have growth at the extreme ends of the (socioeconomic) scale and constriction in the middle, that presents some challenges that are reflected in both the class structure and in the trajectories of neighborhood-based change

- Third would be that the pace of change in a city like Charlotte is so rapid we’re often placed in a reactive position.

Q. What would make Charlotte more of a global city?

A. More corporate headquarters. Even greater internationalization. A stronger, more solidified role on the national and international landscape. Foreign direct investment. Greater depth and array of cultural institutions, attracting national and international visitors. We’re moving in that direction, absolutely. And not only are we getting more of these things, we’re also thinking strategically about where they should be. We’re concentrating a significant amount of the cultural, human and other capital uptown, in much the same way cities like London New York, Paris and Toronto would do.

Q. What demographic changes in the Charlotte region are most surprising to people who don’t keep up with such statistics?

A. Absolutely, the growth of the foreign-born and its diversity. That demographic change is something I think most people are surprised to hear about. They know it’s there because they’re reading the paper, they see and hear people speaking other languages in their grocery stores, but they’re not encountering it yet on a daily basis. When that occurs, I think people will be less surprised. We’re right on the cusp of that, but it hasn’t occurred quite yet.

Q. How has the economic downturn affected the immigrant community in the Charlotte region?

A. In both expected and unexpected ways.

There has been a constriction of the range and depth of job opportunities, particularly in sectors where, for example, the most newly arrived Latino immigrants find work: Construction, landscaping, maybe some constriction in personal services. That’s something we’ve expected.

The expected reaction was (immigrants) would leave, and that wasn’t the case. Some did, but we didn’t have an exodus.

If there are no jobs or the opportunity is narrowing, why are they still here? Some don’t have the resources to go anywhere else. Or they’ve made a commitment to our community and want to stay. Many of them have families established here.

Charlotte continues – there are obviously some exceptions – to be a place that works hard to be inclusive. I think that is also an important factor. The anti-immigrant sentiment that exists in other communities definitely exists here, but is somewhat tempered by the fact this is a globalizing city and there is recognition on many levels that the success of this city is made up of lots of small puzzle pieces. Immigrant labor, the growing foreign-born population and the growing international connectivity are certainly an important part of that puzzle.

Q. What made Charlotte successful in attracting the Democratic National Convention?

A. I’m not surprised they chose Charlotte, because Charlotte is a globalizing city that is on the rise. When (Pew Hispanic Center founder) Roberto Suro gave the keynote address here at a conference a few years ago, he began by saying, “When people look back at the history of immigration in this country in the 21st century, Charlotte is going to be one of these cities they’re going to be pinpointing … ” It’s one of the cities at the vanguard of this process. Within the last 10 to 15 years, Charlotte has become a city that is not one you discover after you’ve arrived to the United States. It’s your first choice.

We continue to be a leading banking center, nationally and internationally.

We are not growing just because of foreign-born settlement. We are also a settlement location for people moving from other parts of the United States. People are coming here despite the high unemployment numbers. That speaks to people’s optimism about what’s going on here, even in the economic downturn.

There are obviously the political reasons the DNC chose to come to the Carolinas, but beyond those, I think it makes sense for them to be here at this time in this city.

Q. What factors make you refer to Charlotte as an unconventional city to host a political convention?

A. It’s not one of the nation’s premier cities. We are a city on the rise. Conventions are normally held in cities that have a higher profile.

The way in which things are done in Charlotte is somewhat unconventional. For example, in traditional gateway cities, immigrants would arrive, settle in the poorest, most impoverished communities close to the center city and make their lives there. As they increased their socioeconomic capital, they would move out into the suburbs. In Charlotte, that’s not the case. The vast majority of the immigrant population is moving straight into the suburbs.

The way in which we have gone about revitalizing our center city is also unconventional. In Charlotte, it was not organic. It was very deliberate, led by the banks in partnership with the city and other groups. That’s now common, but in 1973, that was not common at all.

We often think of globalization as something that just happens to cities. Charlotte is a place where globalization is clearly affecting the city, but at the same time, the uniqueness and strength of Charlotte and the Southern identity kind of melds with globalization in a way that creates a slightly new form, something that may well be distinctive to this place.

Q. You’ve done work on barriers to economic and social success that immigrants in Charlotte face. What could be done to eliminate those barriers?

A. Most of my local work in that regard has to do with access to primary health care. For the last four or five years, I’ve been a member of Mecklenburg Area Partnership for Primary-care Research (MAPPR), which works to identify and better understand barriers to primary health care for Charlotte’s Latino population. Our work has identified language, cost, things you would expect. But there are other barriers that come with being a newcomer in an urban community particularly when you have come from a rural community in a less developed country as many of most recent Latino immigrants have. One barrier is not knowing how to navigate a city. You don’t know where you should go to get basic foods, to get basic medicine. You don’t know that in this country, the way to most affordably get health care is to first see a primary care doctor, because you’ve come from a community where, when you see the big, red cross that’s where you go for everything: the flu, a broken leg, when you’re having a baby. There isn’t any mechanism to help you understand the system here, so you go to the emergency room – the place with the big, red cross. MAPPR’s goal is ultimately to improve the health of the overall community. If you understand how to access health care, how to enroll your children in school, that you should seatbelt them in cars, how to use public transit, what kind of documents you need to get work, where you go when you feel you are being treated unfairly, those things help people more rapidly become settled, functioning, contributing members of the community.