Neighborhood schools? More city parents are taking a fresh look

In Charlotte’s Madison Park neighborhood, Gretchen Gregg didn’t search for a magnet school, a charter school or a private school when her daughter entered kindergarten last fall. She enrolled her at the neighborhood public school, Pinewood Elementary, even though many parents in her middle-income community refuse to send their children there.

In Sedgefield, another older neighborhood attracting an increasing number of young professionals who want to live near uptown, some parents have been meeting for more than a year to rally support for Sedgefield Elementary. Like Pinewood, it has low test scores, a high percentage of students who receive free or reduced-price lunch and a low percentage of white students.

In the Stonehaven and Medearis communities off Monroe Road, Rama Road Elementary PTA President Robin Freeman helped create T-shirts reading “Rama Proud” to promote school pride and started a spring festival three years ago to lure neighbors to the campus. She and offers tours to any parents who want to see the school. Both her children, in first and fourth grades, attend the school.

“We love that school,” said Freeman, 39, a fitness instructor. “Most parents have never been to Rama Road and go on hearsay. They just know it’s a Title I school. That just means it’s a high-poverty school. It doesn’t mean they are bad kids.”

In at least a half-dozen older Charlotte neighborhoods – where in recent decades many white, middle-income families have shied from sending their children to neighborhood schools with a preponderance of low-income, minority students – some young professional parents are taking a closer look at these public schools. Some say they don’t want, or can’t afford, to move to more distant, more affluent suburban neighborhoods where school populations are overwhelmingly white. Some say they want their children to go to class with friends who live up the street. Another factor that has some families considering their neighborhood schools: Starting in fall 2013, they’re losing a federal opt-out feature that let families assigned to low-performing schools send their children elsewhere.

|

Want to know more? Parents in Commonwealth Morningside neighborhood eye a neighborhood school many have avoided. Read article. School attendance zones aren’t the same as neighborhood boundaries. Click here for a map of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools attendance zones. Learn more about Madison Park, Sedgefield and Stonehaven neighborhoods. See below. |

The phenomenon of middle-income, white families avoiding certain neighborhoods due to discomfort with public school choices can affect property values and neighborhood stability. A turn-around in parental attitudes toward nearby schools could be a significant turning point for a number of Charlotte neighborhoods poised for revitalization.

Parents’ discussions about how to improve neighborhood schools often come with suggestions to add partial or full-magnet programs to attract parents, or to redraw boundaries to send children to high schools closer to home. Those proposals are surfacing as a new, countywide discussion gets under way on the future direction of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. Newly arrived Superintendent Heath Morrison recently named more than a dozen task forces and is seeking public comment on issues ranging from the closure of schools in predominantly black neighborhoods to programs for gifted and talented students.

“It is vital to our success as a community that parents can look down the street and think that their child can get a quality education,” said Tyler Ream, CMS’ superintendent for the Central Elementary Zone. He oversees all the city’s Title I, high-poverty elementary schools. “Most of the parents [focusing on neighborhood schools] have a long-term vision for where we should be as a community, and they are dissatisfied. They are holding us accountable for the things we profess. I see that as a catalyst for change.”

School officials and the community, he said, will have to be thoughtful and careful about expectations and setting priorities. “We need to work with parents and really communicate,” he said. “We have to be careful in how we move forward.”

Neighborhood organizers trying to get parents to enroll their children at neighborhood schools often mention the success of Plaza Midwood residents in helping improve Shamrock Gardens Elementary, where the addition of a partial magnet program helped lure more Plaza Midwood families.

Parents in the nearby Commonwealth Morningside neighborhood off Central Avenue and in the Sedgefield and Montclaire communities are also seeking a magnet or partial magnet program for their neighborhood schools. (Read more about the Commonwealth Morningside effort in “Neighborhood wrestles with school dilemma.”)

Working for change in Madison Park

In Madison Park, a neighborhood of small 1950s and ’60s ranch houses and more than 4,000 people, residents are promoting Pinewood Elementary but also are focusing on the high school attendance zone.

Nine years ago, health care professional Jarrett Hunt, 33, and his wife moved to the neighborhood, which lies between Park Road and South Boulevard, and between Woodlawn and Tyvola roads. He began volunteering at Pinewood and became one of the leaders of an effort to improve the school around the time his 2-year-old was born. The neighborhood association won a $25,000 city matching grant to turn the vacant site where the old Pinewood school building had been demolished into a neighborhood park. It bought signs supporting Pinewood, and residents put them in their yards. Parents also have helped plant school gardens and win money and donations for other school needs.

“The community is really engaged and we see the potential at Pinewood,” he said.

According to principal Trish Sexton, residents and parents have developed a strong partnership with Pinewood, where 91 of approximately 550 students live in Madison Park, which is predominantly white. Test scores at the school, which is about 80 percent Hispanic and African American, have been increasing for all students.

“We’ve been pleased with Pinewood,” said Gretchen Gregg, who moved into Madison Park last September. “The teachers are great. The children have access to a lot of technology. My hope is that more people will decide to send their children to our neighborhood school and make it better.”

While he still supports Pinewood, Hunt says he is disappointed by a recent decision to reassign Madison Park high school students to Harding High, 10 miles away. He thinks the students should attend a closer high school, Myers Park or South Mecklenburg.

“We’re offering to help turn around the elementary school,” Hunt said. “But parents are saying why should we put up the effort when CMS isn’t working with us on the high school.” He said he is so discouraged by the high school situation that he doesn’t know where he’ll enroll his sons, a newborn and a 2-year-old.

“You won’t find anyone who is more of a public school supporter than me,” he said. “But I have to look at what I’m going to do. I just don’t know at this point.”

Moving beyond the fear

Sharon Thorsland agonized over whether to enroll her twins in kindergarten last fall at Sedgefield Elementary.

For more than a year, Thorsland, 43, a part-time radio sports reporter, has been heavily involved in learning about her neighborhood’s namesake elementary school and helping build support for enrolling there.

A group of parents in Sedgefield, south of the Dilworth neighborhood and lying between Park Road and South Boulevard, met with the principals and teachers and toured the school. Someone created a “Support Sedgefield” Facebook page. The parents talked about their fear of sending their white children to a school where they would be in the minority, so a representative of the Levine Museum of the New South was invited to a meeting to discuss the courage of black families who had to overcome similar anxieties during desegregation. Sedgefield Elementary’s student population is more than 90 percent African-American and Hispanic.

The goal was to get at least five families to say yes. Ultimately, none of the parents attending the meetings enrolled their children last fall.

“Nobody took the plunge,” said Thorsland, who sent her twins to a magnet program at Elizabeth Traditional Elementary, feeling its structure would better fit their needs. “I don’t have a problem with diversity. But I’ll be honest, they would have been in an extreme minority. ”

Thorsland, meanwhile, said she continues to rally support for Sedgefield and will be working to convince CMS to start a partial magnet program, to give parents an “extra push.”

“We think CMS is at a crossroads,” she said. “We think Dr. Morrison can shake things up and do things differently. I think this is a perfect opportunity to make some changes and bring people back to CMS.”

Expecting a good experience and education

Ten years ago, Doug Caldwell and his wife moved into Stonehaven, knowing they wanted to support their neighborhood elementary school, Rama Road Elementary, despite having heard it was not the best. The neighborhood of homes built mostly in the 1950s is nestled off Rama and Sardis roads.

Caldwell, 37, who works in social media marketing, began meeting with the principal and helped organize informational meetings to help other parents find out about the school’s priorities and how it is using its federal Title I funding to benefit the students. The school’s population is about 80 percent African-American and Hispanic. “We had open and honest conversations, peeling back all the myths,” he said.

He has decided to enroll his 4-year-old daughter in kindergarten at Rama Road in the fall.

“I’m excited about my daughter experiencing interaction with diverse cultures, for personal growth and life enrichment,” he said. He is satisfied, he said, that students who excel as well as those who are struggling will get the attention they need from teachers. And, while the test scores are weaker than at some other schools, he said he believes Rama Road has a strong principal and teachers.

“We’re convicted enough to support our neighborhood school,” Caldwell said. “My hope and expectation is that it will be a good experience.”

Learn more about Madison Park, Sedgefield and Stonehaven neighborhoods

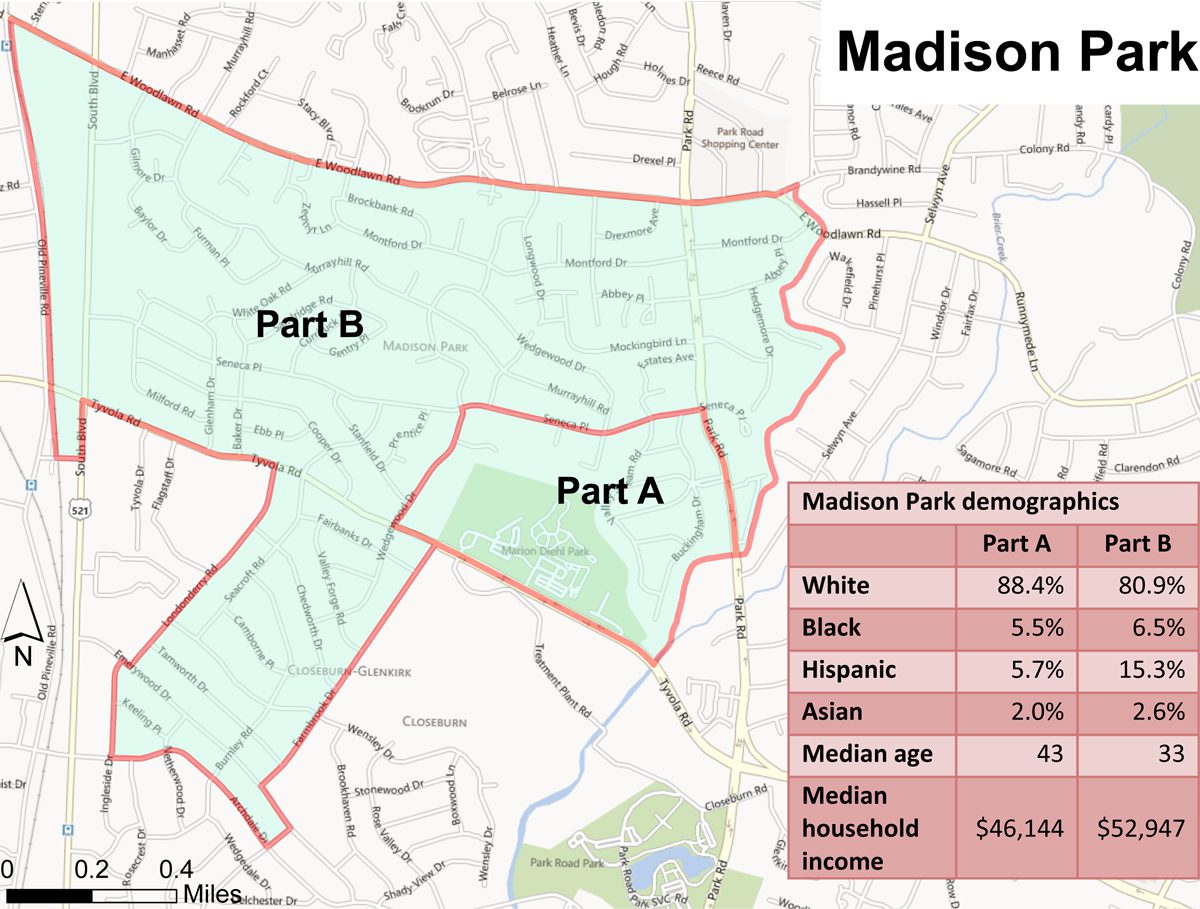

The charts and maps below give demographic information about the three neighborhoods, taken from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Neighborhood Quality of Life Dashboard. In the dashboard, which offers up-to-date information about all Charlotte neighborhoods, many neighborhoods are made up of more than one statistical area. Madison Park is made up of two, Stonehaven covers three. The maps and charts below show the different statistical areas that make up each neighborhood. Click on each chart for a larger view.