Four things I wish I’d known about Charlotte transit before I started writing about it

Charlotte’s path forward on transit is murky. It’s unclear when or if we’ll have a vote on a new, one-cent sales tax. No one knows how to revive the stalled Red Line commuter rail. And with driver shortages and service cuts, bus ridership is in free-fall.

As we talk about how to move ahead, it’s more important than ever to have a common baseline and understanding of transit in Charlotte — what its goals are, how we pay for it now, who rides it and where. Watching the debates around transit in our community, I’ve noticed a few recurring misconceptions that keep bubbling up.

All of this got me thinking about my tender days covering transportation as a young reporter at the Charlotte Observer (I wrote about transit, growth and development in Charlotte going back to the mid-2010s). There was a lot I didn’t know, much of which I had to learn via corrections or snarky Twitter replies to my work.

Here are four things I wish I’d known about transit in Charlotte before I started writing about it. Maybe you already know some of these. Maybe you’ll learn something new. At the very least, I hope I can save you from a snarky Twitter reply or two.

Fares just aren’t that important

When I started writing about transit and transportation, I assumed that fares — money you put into the farebox or use to purchase a ticket — paid for most of the system’s operating costs. But fares are a comparatively small piece of the revenue picture for the Charlotte Area Transit System. And with ridership still in a crater post-pandemic, fares have become even less important.

Most of CATS’ operating budget comes from the half-cent transit sales tax applied to purchases in Mecklenburg County. Even people who know that often don’t know quite how little fares contribute to CATS’ revenue.

Consider: In fiscal 2023, CATS’ total operating budget is $211 million. But CATS is projected to collect only $13.4 million in fares.

More than half of CATS’ operating budget comes from the sales tax (this year, CATS is expecting to receive $135 million). The rest comes from a mix of sources including federal funds, pandemic relief money and advertising revenue.

Understanding the relative insignificance of fares as a revenue source for CATS is key to understanding why proposals like making the transit system free aren’t that far-fetched. And it’s also key to understanding why CATS can’t simply raise fares to cover the cost of its planned multi-billion dollar expansion (and why the system doesn’t seem too worried that many fareboxes are broken).

Trains get the glory, buses get the job done

OK, that subhead is a slight exaggeration. But if you’ve lived in Charlotte for any length of time, you’ve seen the dramatic and much-celebrated opening of the Blue Line light rail and the Blue Line extension to UNC Charlotte. And in the $13.5 billion Charlotte Moves expansion plan, the single biggest, and costliest, item is the east-west Silver Line.

All of the focus on rail has obscured a simple fact in Charlotte, however: Buses have historically carried the lion’s share of passengers. In 2018, the last full pre-pandemic year, federal statistics show the Blue Line light rail carried 7.1 million passengers. Local buses carried 14.9 million.

“Without an adequate bus system you cannot have an adequate mass transit system,” said Mayor Vi Lyles in 2021.

So why the disproportionate focus on trains? To some degree, it likely reflects deep biases. There’s a longstanding stigma around riding the bus. Many people associate buses with riders who don’t have a choice and use transit as a last resort. On CATS, bus riders are more likely to be low-income (34%) and minority (68%) than light rail riders (15% and 49%, respectively), according to a 2017 CATS study.

As bus ridership continues falling, however, the historic imbalance in ridership might be reversing. In June, CATS local buses carried 380,972 passengers. The Blue Line carried 395,059 — which appears to be the first time the Blue Line ever carried more passengers in a month than local buses. (For comparison, in March of 2020, right as the pandemic was starting, CATS local buses accounted for 709,277 passengers, while the Blue Line carried 471,880).

So, why don’t we just take all the money we’re thinking about spending on trains and buy the world’s biggest bus fleet? That leads to the next thing I wish I’d known…

Transit is about economic development, not just moving people

While it might seem like transit is mostly about moving people from Point A to Point B, don’t underestimate the importance of building booms that accompany new transit projects. All you have to do is compare South End pre-Blue Line to South End now.

And trains signify a level of permanence that buses simply don’t. You can’t move the rails, after all. A new rail line is a highly visible signal that investment is coming. So, of course policymakers love trains. What other magic elixir can transform barren blocks of old industrial buildings into a gleaming, second skyline in just a decade and a half?

City Council member Tariq Bokhari framed the issue succinctly at a planning retreat last year.

“Look back at that Blue Line. I think the impact that that has made on transit in the city compared to that of the impact it’s made on economic development is a rounding error,” he said. “When you look at the number of people it moves a day versus the economic impact and the transformation it had on South End, it was an economic bet.”

Understanding the premium local decision makers place on the economic development impact trains can have is key to understanding the local discussion around transit expansion. The hope of creating the next South End is driving decisions around where to route the Silver Line (such as CATS’ plan to push the line through the less-developed northern part of uptown instead of bringing it through Trade and Tryon Streets).

Trains are also generally faster and more reliable than buses, since they don’t get caught in traffic. But if you think the transit expansion is only — or even primarily — about moving people and alleviating congestion, you’re missing a big part of the picture.

CATS bus drivers don’t work for CATS

OK, after all the chaos lately in the bus system, this last one is definitely more widely known than it used to be. But when I started covering transit, I had no idea that CATS bus drivers actually work for an independent, private company.

The reasons are complex, but they basically boil down to this: Before 1976, transit was private in Charlotte. When the city got into the business, acquiring buses and operating routes, federal rules required that unionized drivers maintain their union status. But North Carolina state rules forbid cities from negotiating with unions.

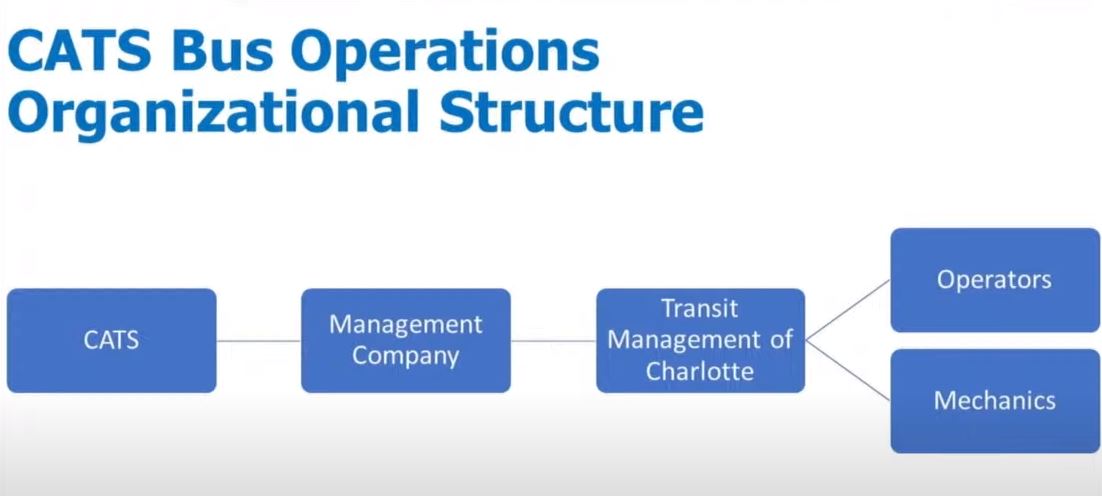

So, ever since, bus drivers have been employed by private companies hired to run the city-funded bus system. Bus drivers belong to the SMART Transportation Division Local 1715 union, and are technically employed by a company called Transit Management of Charlotte. A third-party management company — currently RATP Dev USA — operates that firm.

RATP Dev is responsible for overseeing, operating and maintaining the bus system, including supervising all of the bus operators and mechanics. The city renewed its contract with RATP Dev in 2019.

CATS’ bus system structure is complicated. City of Charlotte graphic.

It’s not a secret, but it’s not exactly common knowledge that CATS pays a private company to run its buses. Even some City Council members were surprised to learn the extent of RATP Dev’s responsibility for running CATS’ bus system, a recent WBTV story found.

The workaround can lead to some convoluted situations. For example, City Council member Larken Egleston asked in July whether RATP Dev officials could come talk to them about the challenges facing the bus system and potential solutions.

“Given the role that RATP Dev plays in a lot of this and the control they exercise…would it be useful for us to have leadership from RATP Dev at our August committee meeting?” he asked.

But since RATP Dev is in the midst of negotiating a new contract with bus drivers and the SMART union, CATS chief executive John Lewis said that wasn’t a good idea.

“Once the collective bargaining process is complete, I think that would be an option,” said Lewis.

That effectively leaves City Council in the awkward position of trying to figure out how to fix its bus system without being able to talk to the actual company operating it.

There you have it: The four things I wish I’d known at the beginning, rather than figuring out along the way. No one knows where Charlotte’s transit system is headed. But if we can get on the same page and talk about it without making the same misconceptions, we might have a better chance of figuring out how to get there.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Transit Time, a collaborative newsletter produced by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, WFAE 90.7 and the Charlotte Ledger.