Are bus-only lanes a key part of Charlotte’s transit future?

This story is part of the Transit Time newsletter, a partnership between the Urban Institute, the Charlotte Ledger and WFAE. Find out more and subscribe here.

For six months, commuters and residents near Central Avenue in east Charlotte faced an unfamiliar sight: “BUS ONLY” emblazoned on one general-purpose lane in each direction, in the city’s first large-scale experiment with giving buses priority over cars.

It’s an idea the city is now considering on other busy bus corridors throughout Charlotte. On Central Avenue, transit advocates and riders were excited to see a new tactic tried in a Sun Belt city that’s long grown by following private cars into the sprawling suburbs.

But many nearby residents and drivers recoiled, amassing more than 1,200 signatures on a petition against the bus-only lanes and speaking out at City Council forums. Depending on who you listened to, the program was either a godsend or abhorrent, a progressive look at what the future of transportation could hold or an unnecessary imposition on an already traffic-clogged thoroughfare.

The pilot project ended in March, opening the lanes back up to cars from Eastway Drive to the former Eastland Mall site. Charlotte Area Transit System officials stressed that was always the plan, despite some earlier chatter about extending the bus-only lane to uptown. Transit planners are studying bus-only lanes and other measures that would give buses priority over general traffic, like streetlights that stay green longer to let buses through.

“We identified what worked well and what didn’t work well,” said Bruce Jones, a transit planner with CATS. “One of the things we’re looking at is how can we bring similar features to our bus network… we’ll be taking a look at which candidates we recommend to the public for priority treatment.”

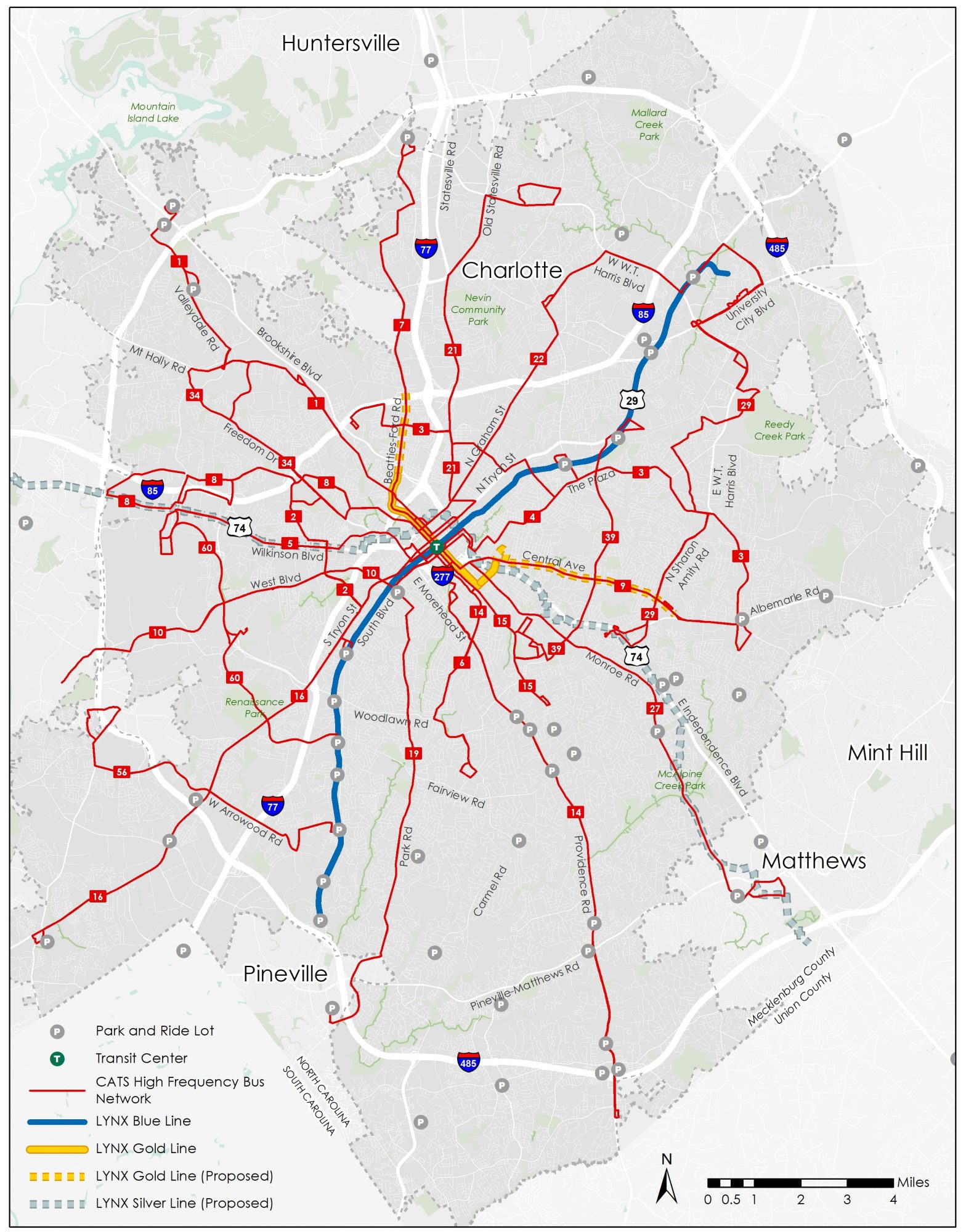

This month, CATS is launching a study of high-traffic bus corridors across the city to identify other locations that might be a good fit for such measures. That could mean giving priority to buses — in their own lane or via other means — on congested streets like Providence Road, Freedom Drive and, Park Road and Pineville-Matthews Road. The transit agency will present its recommendations in early 2022.

But if opposition to the Central Avenue pilot is any indication, CATS could face a tough road ahead to prioritize buses on city streets.

Charlie Welch, president of the Myers Park Homeowners Association, said that on a fast-growing corridor like Providence Road (one of the study’s subjects), the city should be looking at much more than bus prioritization to get traffic moving and serve residents’ needs. Without a holistic approach — one that includes trees, sidewalks and all transportation modes — Welch said rallying neighborhood support would be difficult.

“I think before we do anything to it, we need a master plan of what that road will look like,” said Welch.

CATS has high-frequency bus routes on many of Charlotte’s corridors.

The transit agency is trying to lure riders back to its bus system, and not just because of Covid. Ridership was falling for years before the pandemic, despite the Envision My Ride program to increase frequencies on key routes.

It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem: Transit officials say that until buses are as reliable as trains, with their own right-of-way, 15-minute or better frequencies and the certainty that you won’t be stuck in traffic, they’re not attractive to riders who have the choice to drive. Still, until lots more people choose to ride the bus, taking a general purpose lane on a crowded road and giving it to buses looks to many drivers like an unfair deal.

“There is so much development in that area and more to come. Traffic is already bad. Reducing the lanes on Central Ave. would be a nightmare,” said one of the petitioners opposing the lanes on Change.org.

Another wrote: “It makes no sense to create traffic backups for cars so a bus that only comes every few minutes can have an entire lane to itself.”

Limited options to boost transit

Trains get the headlines and the multibillion-dollar investments, but getting Charlotte’s bus system in shape might just be the most important thing the city can do for transit.

Rail lines are lauded for spurring billions in development and transforming whole swaths of the city, from South End to University City. But more people ride the bus than the Blue Line, a trend that’s been exacerbated by the pandemic: Year-over-year light rail ridership is down more than 71%, while bus ridership is only down 49%.

Buses have racked up more than twice as many rides already this year — 3.3 million vs. 1.5 million – likely because many bus riders are essential workers while light rail riders are more likely to be uptown professionals who’ve been able to work from home.

“A disproportionate number of people who ride the bus are more likely to be Black or brown, and more likely to be low income,” said Krissy Oechslin, chair of the Transit Services Advisory Committee.

“Buses get no respect,” said Oechslin, who also rides the No. 9 bus down Central Avenue. It’s the city’s busiest local bus route.

Respect or not, getting more people to ride the bus might be Charlotte’s only realistic option to expand transit along traffic-choked streets like Providence Road. There’s no realistic way to widen such roads, nowhere to put light rail, and the proposed Silver Line (running east-west) won’t help most workers heading in to the office along those routes.

With CATS’ proposed one-cent sales tax on hiatus until at least 2022 (when the state legislature might authorize a referendum in the election that’s been delayed by missing Census data, though that’s far from certain), fixing up the bus system might be all Charlotte has funding to do, at least for a while.

Bus trip times have been getting longer for years as congestion worsens in Charlotte. On two busy routes (Eastway Drive to uptown and Rosa Parks Place to uptown), average round-trip times have increased by about 10 minutes since 2010, according to CATS.

Jones, the transportation planner, said the bus-only pilot lane shaved about 30 seconds average travel time from the No. 9 bus route on Central Avenue. He pointed out that it was a short stretch, and that traffic volumes were down anyway because of the pandemic (which also made this an attractive time to try a disruptive pilot program on a busy road). Still, Jones said rider surveys indicated that No. 9 riders were satisfied with the change and wanted to see more.

The pilot program indicated that bus travel times and reliability can be improved by a bus-only lane, Jones said. And riders liked it. But given community pushback and confusion among some drivers, he said CATS also learned they need to do more community outreach and education.

“A bus only lane won’t work on every corridor. There’s other techniques we can utilize as we speed up service,” said Jones, pointing to special pull-outs for buses to get around lines of traffic at streetlights, signaling devices to changes lights or keep them green so buses can get through, and changing the placement of bus stops to make them more efficient and faster.

Jones said many drivers weren’t sure what to do when they saw bus-only lanes, which have previously only been implemented locally on a couple blocks of Fourth Street uptown. Others treated the car-free lanes as a convenient way to speed around traffic.

“One of the lessons learned is we can continue to educate individuals,” said Jones.

Meg Fencil, program coordinator for Sustain Charlotte, agreed that education is part of the problem.

“I think the challenge is really that the public didn’t understand the lane within the larger context of the whole system,” she said. But, she added: “If they (CATS) just put more frequent buses on the road, they’re just going to get stuck in traffic.”

Speaking to City Council during meetings this spring, nearby residents made clear that one of their chief complaints was that they didn’t feel like they had a voice in the process.

“This exhausting experimental program was executed against us with no input,” said Heather King, who pleaded with City Council to “stop the insanity.”

“Simply return us what we once had, which was four operational lanes with a turning lane,” she pleaded.

Heather Ferguson, a 20-year resident of east Charlotte, told City Council that neighbors weren’t consulted before the lanes’ installation.

“We are not your guinea pigs, and yet we were treated as such when those lanes were put in with no public input and no regard for traffic and public safety,” she said.

Jones said CATS officials appreciates comments from all quarters, not just transit riders.

“We did receive a lot of input from individuals that are traveling by car,” Jones said. “All of it was valuable.”

Without a more efficient bus system, Maureen Gilewski said she fears large parts of Charlotte in the wedges between the city’s planned light rail lines will remain stuck in their auto-centric mode forever.

“It’s been hard for me to stomach” the opposition, said Gilewski, a longtime east Charlotte resident and leader in the CharlotteEAST neighborhood coalition.

The No. 39 bus in northeast Charlotte. Photo: Martin Zimmerman

Covid wildcard remains

The same unknown that’s hanging over everything these days looms over the future of transit and commuting in Charlotte: Covid. Pre-pandemic, about 75% of Charlotteans drove to work alone, while roughly half the workers in Mecklenburg commuted in from another county.

Now, with long-term work-from-home or hybrid schedules becoming a reality, it’s still unclear what “rush hour” will actually look like when the world gets back to normal.

But for Oechslin, chair of the transit advisory commission, reaction to the bus-only lane pilot on Central has left her discouraged about the prospect for more throughout the city.

“If you can’t put a bus lane on the most frequent, most popular bus route, where can you?” she asked. “This was supposed to be the easy test, and the next part was going to be the uphill battle.”