2024 Schul Forum Opening Comments

On Feb. 1 at our annual Schul Forum, more than 175 Charlotte residents, neighbors and friends, along with national and local experts, explored the implications of recent research that suggests that economic connectedness, a form of social capital, is connected to upward economic mobility. Dr. Lori Thomas, Executive Director of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and Charlotte Regional Data Trust, opened the Forum with these comments:

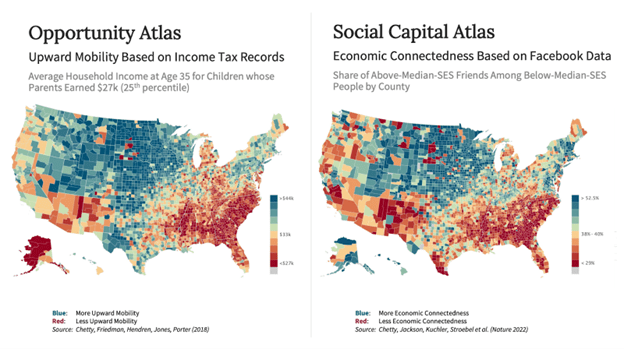

As you’ve read, we have connected this year’s Schul Forum to the work of the Opportunity Insights research team, led by Dr. Raj Chetty at Harvard University, who visited the university this Fall as a part of the Chancellor’s Speaker’s Series. I need to tell no one in this room that the research the Chetty team released a decade ago has become a touchstone for our community (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force, 2017). We were reminded in 2013 that despite many measures of economic prosperity – often leading in the South and in the country – our area was one of the most difficult metro areas in the country for a child to rise out of poverty. In that study, the Chetty team’s work pointed to five factors that related to our lack of shared mobility – segregation by race and income, income inequality, measures of K-12 school quality, family structure, and social capital (Chetty et al., 2014). All interdependent, each multifaceted and related to how we understand and view ourselves, how we relate to one another, and crucially how we structure the organizations, institutions, and sectors around us. It’s that last factor – social capital – that we’re focusing on at this year’s forum, the subject of some of the Chetty team’s more recent research. The researchers used extensive, de-identified Facebook data on over 72 million people to test several hypotheses about social capital and how it is related to economic mobility. They found that two typical measures of social capital including the extent of our friendship networks, or social cohesion, or Civic engagement – like our rates of volunteering were not as closely tied to economic mobility, as was a third type of social capital – the way we connect to each other across class, a term the researchers called economic connectedness. In fact, they found that economic connectedness was one of the strongest predictors of economic mobility that we know of, explaining more about economic mobility than any other factor studied thus far (Chetty et al., 2022a). And if you look at this screengrab from Dr. Chetty’s recent visit to campus you can see how closely the two concepts are related. In the map on the left, the darker blue means greater upward economic mobility, the red means less. In the map on the right, the Blue means more economic connectedness, the red means less. Research hasn’t outlined all the causes of what we are seeing in these maps, but the work has demonstrated that connecting across class matters for economic mobility.

But is it enough to simply put rich people and poor people together in a neighborhood or in a school or in a city?

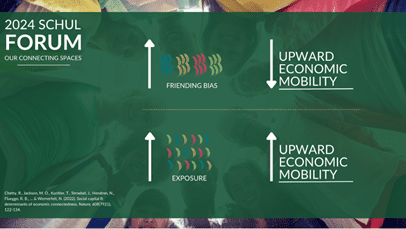

You’ve heard the phrase “birds of a feather, flock together” – describing a well-documented tendency of people to befriend those like themselves (see Miller et al., 2022). Just being in a diverse place isn’t enough because what the Chetty team termed “friending bias” limits the benefit we would otherwise gain from those cross-class connections. So, in diverse settings, the more friending bias there was, the less the diversity mattered for economic mobility. In fact, the researchers found that it cut the impact of economic connectedness in half. But the places that were diverse and people had more exposure to class differences and less friending bias, the better the economic mobility for those with lower incomes (Chetty et al., 2002b).

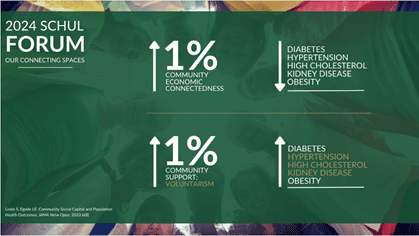

And this is not just about economic mobility. The way we connect matters for other outcomes, too. Using the Chetty team’s social capital data, which in aggregate form is publicly available, a study found that higher levels of economic connectedness were associated with higher levels of entrepreneurial activity (Patel & Wolfe, 2023). And in a study of population health and social capital across the nearly 18,000 zip code tabulation areas of the United States, for every 1% increase in economic connectedness there were significant decreases in a range of chronic diseases. And interestingly for other forms of social capital like formal helping relationships and voluntarism, more of that was not necessarily a good thing for population health (Linde & Egede, 2023). I’m a social worker by training – we have to sit with that.

It matters that we connect and how we connect in our spaces. It’s not enough to co-locate.

I don’t know about you, but there’s stuff here that makes me pretty uncomfortable and I’m going to share a few of those discomforts with you – First, these connections aren’t easy and if you are Black or Latinx, if you are indigenous or an immigrant, or if you are a part of any group that has been historically othered, connecting may not be psychologically or physically safe and befriending those who are most like you, may be your safety and sanctuary, as the Black church has functioned in this country. There is a robust literature that warns of the danger of rushing to unity without reckoning with what divides us. There is much in the ground that we still have to sit with and I’m not comfortable with the potential for oversimplification or moving past reckonings and reconciliations that are incomplete. Second, as a first generation college student, who made it through higher education on Pell grants and student loans, and as the daughter of a union machinist in a one-income household in Appalachia, I was aware of class before I was aware of much else, and I still bristle at, again, oversimplified notions that we simply put rich people together with poor people to fix it all, to me an echo of our worst manifestations of charity. And third, we are 25,442-units short of affordable and available housing in Mecklenburg County for households earning less than 30% of the area median income or less than $30,000 for a family of 4, 50,000 units short if you count Concord and Gastonia. How can we talk about the “soft work” when there are houses to be built and decent jobs created and schools funded? But I can also give you three reasons I get excited and maybe even have hope in this work. First, this work is actually suggesting that the type of social capital that really matters and makes material difference in people’s lives, is not the kind that we tend to interpret as charity, like volunteering or community support of an “other.” If we look deeply at this work, it could actually push us away from the oversimplification of social capital. Second, the work suggests that we must thoughtfully structure our connections, every bit as much as we do our capital stack to create affordable housing, every bit as much as we think of the borders of our school districts. This isn’t just soft, let’s-get-along work, this is the work of building organizations and systems. Structuring for connection is a sea change. And finally, I’ve held onto this since we had our mixed income communities prequel conversation in October. Thanks to Mark Joseph for reminding us of this one – policy comes from people and when we do this connecting work, we till the ground for policy change that can emerge from people shaped by their relationships. In our hyper-divided society, it sounds almost impossible, but it has also never been more fundamental. In that same Schul Conversation in October, Tiffany Capers referenced the work of community building as a Rubik’s cube – multifaceted and complex. And that’s what we’re inviting you into today – bring your concerns, questions, your hopes. The concurrent sessions you are off to next will be the first layer of a conversation that we will add onto during the keynote panel featuring our national guests. Thank you for being here.

References:

- Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force (2017). The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force report. Charlotte, NC: Foundation For The Carolinas.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553-1623.

- Chetty, R., Jackson, M. O., Kuchler, T., Stroebel, J., Hendren, N., Fluegge, R. B., … & Wernerfelt, N. (2022a). Social capital I: Measurement and associations with economic mobility. Nature, 608(7921), 108-121.

- Chetty, R., Jackson, M. O., Kuchler, T., Stroebel, J., Hendren, N., Fluegge, R. B., … & Wernerfelt, N. (2022b). Social capital II: Determinants of economic connectedness. Nature, 608(7921), 122-134.

- Linde, S., & Egede, L. E. (2023). Community Social Capital and Population Health Outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 6(8), e2331087-e2331087.

- Miller, C. C., Katz, J., Paris, F., & Bhatia, A. (2022). Vast New Study Shows a Key to Reducing Poverty: More Friendships Between Rich and Poor. New York Times.

- Patel, P. C., & Wolfe, M. T. (2023). Friends for richer or poorer: Economic connectedness, regional social capital, and county entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Small Business Management, 1-40.