The Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection: Strengthening ties to revitalize communities

[Read the full report here]

It was a cold January day in 2018 when eight researchers from UNC Charlotte’s Urban Institute stepped out into the brisk air in Hamlet, a small town in Richmond County, N.C.

A dusting of snow from a surprise storm the previous day still covered the railroad tracks adjacent to the town’s train station, an immaculately restored Queen Anne structure built in 1900 that once served as a major hub of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad. In its heyday, 30 passenger trains departed daily from Hamlet along five Seaboard lines, compared to 2 Amtrak departures today. One of those lines led to Charlotte, 70 miles to the northwest.

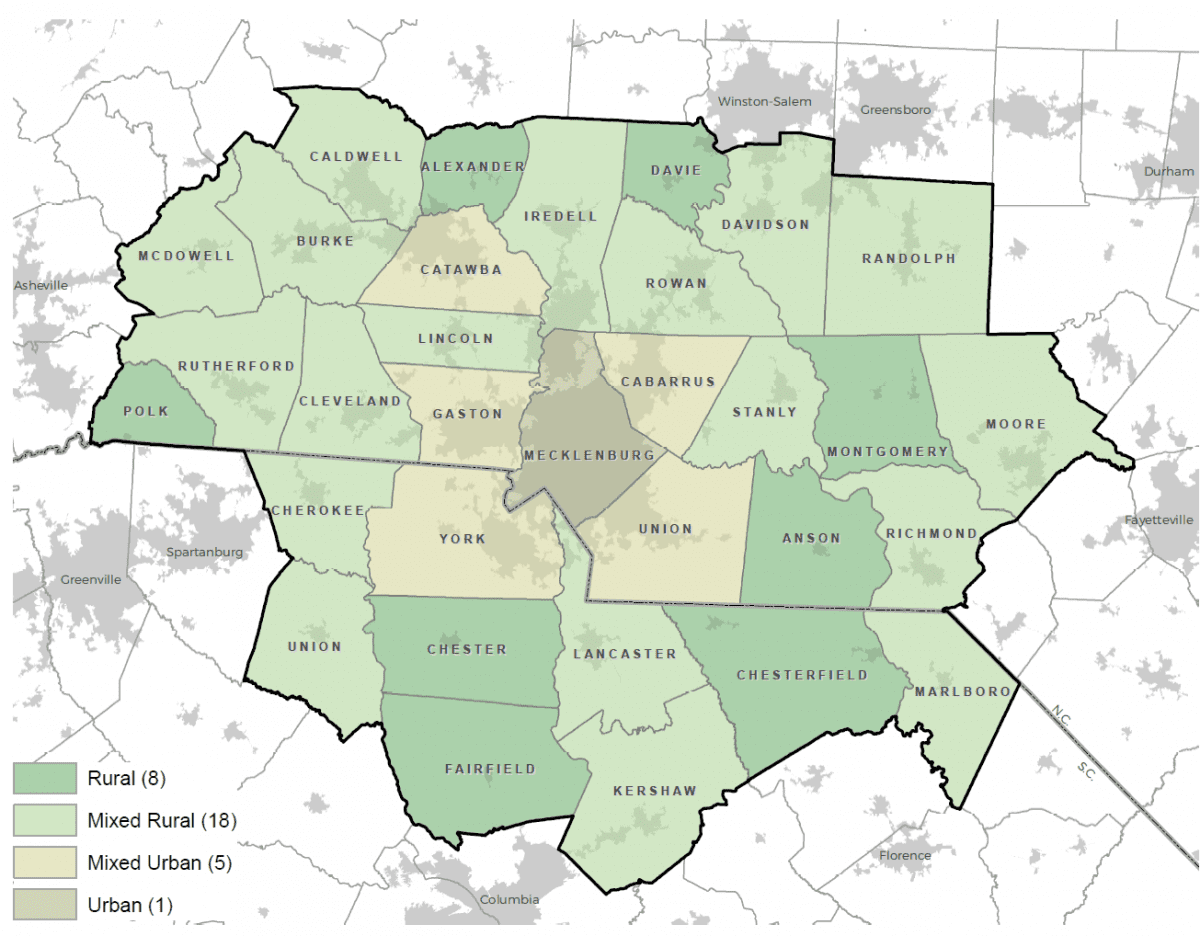

The researchers were there to begin a series of regional tours as part of a new initiative funded by The Duke Endowment, called the Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection project. The project’s aim: To examine what was left, if anything, of the economic and cultural ties that once flourished between Charlotte and surrounding communities such as Hamlet, and to explore whether the foundations built by those relationships were still strong enough to build a new chapter of regional prosperity in the 21st century.

Beginning this week, and continuing through the next three months, the results of that two-year research project will be shared on the Urban Institute’s website. We’ll then discuss and analyze our findings through a series of public forums to be held throughout the fall, culminating in a day-long conference on Nov. 21 in Charlotte that will serve as the institute’s first annual Schul Forum Series.

Today it’s hard for many, especially newcomers, to imagine Charlotte’s interdependence with the small towns and rural communities surrounding Mecklenburg County. But Charlotte’s emergence as a New South city was the result of a manufacturing economy established throughout the region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That economy was mostly built on textiles, with its concentration not in the urban core (as was the case with Pittsburgh’s steel industry or Detroit’s auto sector), but in small towns scattered throughout the Carolina Piedmont – where brick textile mills were built along the banks of the South Fork River in Gaston County and the Great Falls of the Catawba in South Carolina, and along the rail lines that stretched in every direction to places like Kannapolis and Hamlet.

Other forms of manufacturing prospered as well – aluminum to the east where a French company first harnessed the force of the Narrows of the Yadkin to power an aluminum smelter plant (later acquired by Andrew Mellon), and furniture to the northwest, where pioneer wheelwrights adapted woodworking skills developed repairing wagons headed westward into a furniture industry with household names such as Lenoir and Henredon.

And in the spaces between these manufacturing hubs, agriculture provided the raw materials that sustained the region, from the cotton that supplied the mills to the food that nourished the workers and a growing population dependent on their output. Long before “farm-to-fork” became a trendy movement for diners in Charlotte, “buying local” was commonplace, with certain parts of the region even renowned for their agricultural output – the dairy products of northern Iredell County, the celebrated All Star Flour from the rolling wheat fields of Stanly County, and the “Sandhills peaches” from a belt of sandy soil stretching from Candor in Montgomery (N.C.) County, to McBee in Chesterfield (S.C.) County.

Charlotte benefitted immensely from this diverse and interconnected economy. Cameron Morrison, a Rockingham native and North Carolina governor, used his position in the 1920s to build a network of modern roads linking urban and rural markets, giving North Carolina the nickname “the Good Roads State” and underscoring the vital importance of strong urban-rural connections to the economies of both.

Morrison, who eventually moved to Charlotte, and whose family would go on to develop Southpark, Ballantyne and other iconic parts of the city, was typical of the leadership of the times – elected officials and policy makers who understood the needs of both urban and rural communities. Other prominent regional families like the Belks, who started their eponymous department store in Monroe in 1888, also assumed key leadership roles in Charlotte as their businesses grew. John Belk, a scion of the family, was mayor of Charlotte, and Belk family-funded foundations continue to play an important role in regional philanthropy.

By the dawn of the 21st century, however, many of the rural communities around Charlotte were in crisis, even as their urban neighbor was flourishing. While Charlotte had positioned itself to be a national player in the new global, knowledge-based economy – building on the legacy industries that had emerged over the previous hundred years to serve the region’s banking, retail, energy and distribution needs – surrounding communities had begun to suffer from the consequences of globalization, automation, and consolidation in many of the economic sectors that had once sustained the region. Driving through many of the region’s small towns and rural crossroads today, evidence of decline is pervasive, in vacant, abandoned downtown buildings and shuttered textile mills with trees growing from windows and rooftops. Fallow fields are now planted in loblolly pines, in part to maintain favorable tax status for “agricultural use” of the land in an era when few families are still farming.

By strengthening the ties within our region, we can ensure that prosperity is enjoyed by all.

And yet, interspersed with this outward display of decline, our research team found many signs of resiliency, and determination to succeed, in spite of the economic forces arrayed against these communities. Plans to reclaim the rapids of the Great Falls of the Catawba, not for manufacturing, but for a new type of industry – tourism driven by visiting whitewater enthusiasts. A thriving music scene in downtown Shelby, building on the musical traditions first brought to these small towns when rural people left their mountain homes to work in the region’s textile mills. And a new generation of farmers, rediscovering the region’s rich soils and microclimates to serve the growing demand for local foods in nearby urban areas.

The aim of our researchers wasn’t just to document these stirrings of economic renewal, but to explore the possibility of Charlotte joining these communities in their efforts to use place-based strategies to revitalize their economies. After a century of becoming the region’s economic and cultural hub on the backs of these surrounding communities, what is the possibility for Charlotte to “give back” in what Robb Webb at The Duke Endowment’s Rural Church Program calls “a relationship of mutual benefit”?

In the coming months, we will be exploring that question in a series of articles, data visualizations and research papers organized around the themes of “People,” Place,” and “Policy & Practice,” beginning with a series of historical overviews to familiarize readers with the foundations of the region’s interconnectedness. It is our hope that this project will serve as a starting place for reestablishing a sense of regional connection that can help lift the prospects of all communities in the Charlotte region, and serve as a model for other places struggling with the cultural and political consequences of a growing divergence between our urban and rural communities.