A Charlotte primer: A city that thinks big

Welcome, Democrats! You have received loads of material on restaurants, sights and the strange habits of the locals. Here is a primer quick enough for you to digest while you spoon through your breakfast grits.

First and most important, Charlotte is not some other city. It is not by the sea (that’s Charleston), it does not possess a university designed by Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville) or a famous railroad (Chattanooga) and, though some of our politicians are blowhards, this is not the Windy City (Chicago). Once you have solved the “Ch” factor, we can move on – to food.

We have barbecue, livermush and garlic cheese grits (our nod to haute cuisine). They are generally not served together. You probably didn’t know Charlotte was the last capital of the Confederacy or that a naval yard existed here during the War (and if you have to ask which war, you have a lot of learnin’ to do).

We have barbecue, livermush and garlic cheese grits (our nod to haute cuisine). They are generally not served together. You probably didn’t know Charlotte was the last capital of the Confederacy or that a naval yard existed here during the War (and if you have to ask which war, you have a lot of learnin’ to do).

You do know that we are RELIGIOUS. Which is why you can’t order that Bloody Mary with your Sunday brunch until after noon. But be grateful; the booze boundary used to be 1 p.m. until the Carolina Panthers (our NFL franchise) arrived. God, as every Southerner knows, is a big football fan. I’m sure we could ditch this Sunday thing altogether if the Panthers would schedule some morning games. Sports is a religion here.

Charlotte is not Mayberry writ large. We’re not even particularly Southern. We’re American. It is possible to stroll around some parts of the city and not meet a single native Southerner. The Yankee invasion has been so complete that General Sherman would have been paralyzed with wonder. (The vision of an immobile Sherman is quite comforting to many in these parts.)

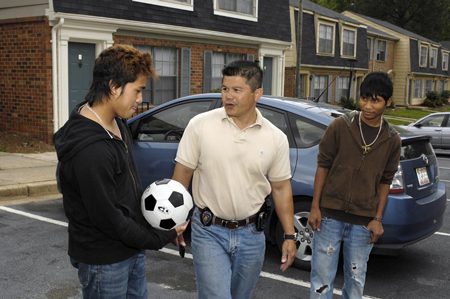

America is an immigrant nation, and Charlotte is increasingly the destination of newcomers from around the world. Hispanic residents (or “Carolatinas”) account for 13 percent of the city’s population, a growth rate of 153 percent since 2000. More than 5 percent of the city’s residents are Asian, a 103 percent increase over 2000. Immigration has done wonders for our cultural and religious diversity, and, thankfully for visitors, significantly upgraded our restaurant scene.

What is most American about Charlotte is its incessant drive for the main chance. This is not Tara and never was. You will feel at home here. Charlotte has always been a welcoming place for outsiders. We have no ossified family social structure. Most of our entrepreneurs came from elsewhere.

What is most American about Charlotte is its incessant drive for the main chance. This is not Tara and never was. You will feel at home here. Charlotte has always been a welcoming place for outsiders. We have no ossified family social structure. Most of our entrepreneurs came from elsewhere.

In the 1870s, Daniel A. Tompkins, a South Carolina-born and New York-trained engineer, settled here. He wondered why all those cotton bales were being loaded on trains bound for the North to be processed into cloth and sold around the world. In less than a generation, Charlotte became the center of a booming textile industry rivaling and eventually passing New England.

The textile industry provided jobs. Southern states had too many people on too little arable land. The mills popping up in Piedmont towns drew workers from as far as the Tennessee and Georgia hills. To northern and foreign firms considering Southern operations, local boosters touted their laborers as hardworking, God-fearing, family-oriented and, above all, uninterested in unions. All was true, except that last part. Workers demanded better pay, better working conditions, less management control over housing, schools and churches, and some measure of job security. Violence erupted periodically in the mills in the late 1920s and early 1930s, as unionization failed. Efforts to unionize in recent decades confronted the decline of the textile industry and the hostility of local business and political leaders. North Carolina remains the least-unionized state.

Though Charlotte had fewer textile mills, it functioned as the industry’s administrative and financial core. The banking network, legal services and insurance companies that textiles required became the city’s economic base and legacy. The predecessor of Bank of America dates from that late 19th-century textile boom, and Charlotte kept growing as a financial hub into the 20th century.

The operating culture in Charlotte is that we think bigger than our size. In the 1920s, the smart money predicted Columbia, S.C., would be the likely place for a new Federal Reserve Bank. After intensive lobbying, the bank wound up in Charlotte. In 1941, Mayor Ben Douglas had the idea to build a major airport here, before demand justified it. Today, Charlotte/Douglas International Airport is a major recruiting tool.

The operating culture in Charlotte is that we think bigger than our size. In the 1920s, the smart money predicted Columbia, S.C., would be the likely place for a new Federal Reserve Bank. After intensive lobbying, the bank wound up in Charlotte. In 1941, Mayor Ben Douglas had the idea to build a major airport here, before demand justified it. Today, Charlotte/Douglas International Airport is a major recruiting tool.

Perhaps Charlotte’s finest hours came during the civil rights era. Two years before the 1964 Civil Rights Act mandated desegregation of public facilities, Charlotte’s white civic leaders came together, and each invited a black counterpart to lunch. Sure, fear that demonstrations could scare off investors likely trumped moral imperatives, but the result set a precedent for reconciling community contention. It set the stage for the desegregation of public schools through busing in the early 1970s. Our accommodation was so successful we sent ambassadors of justice to Boston to tell the Yankees how we handle racial differences down here. Today, we have a black mayor in a city a little more than one-third African American.

In the 1980s and 1990s, we landed NBA and NFL franchises and the headquarters of Bank of America. The nation’s 20th largest city is now its second largest banking center. In the past decade, we have grown a new downtown with 12,000 residents, constructed greenways, built a light rail system and landed the Democratic National Convention. Our openness to outsiders is evident on the names of our many of our institutions; the Levine Museum of the New South and the Blumenthal Performing Arts Center are only two examples.

Charlotte is not Shangri-La. We have problems with some of our public schools, pockets of intractable crime and episodes of political contention. But we have been mostly successful in beating back the forces of provincialism and bigotry. Our economic base relies on a continuous flow of creative and bright people. To many of us, their sexual orientation, gender, race, religion and national origin are irrelevant. You may have heard Charlotte defined as a New South city. But most of all, this is an American city.

David Goldfield is a professor of history at UNC Charlotte. Views expressed here are his and not necessarily the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.