Charlotte wants more walkability. Fast-food companies want more drive-thru-only restaurants. Can they coexist?

Nowhere in Charlotte embodies the city’s awkward and aspirational transition from car-centric Sun Belt suburbia to denser, walkable urbanism quite like a pair of fried chicken restaurants in Cotswold.

Located next to each other near the intersection of Randolph and Sharon Amity roads, Bojangles and Chick-fil-A have both filed rezoning requests to demolish their existing buildings and replace them with restaurants built exclusively for drive-thru customers, with no indoor seating. Chick-Fil-A recently opened another such restaurant on Woodlawn Drive, near a notoriously traffic-choked intersection where the drive-thru line frequently spilled into the road at peak meal times (currently a problem with the Chick-Fil-A on Randolph).

And get ready for more restaurants converting to drive-thru only service post-pandemic, in addition to restaurants like Cook Out and Checkers that have long been mostly drive-up based. After more than a year of shuttered dining rooms, restaurant operators have learned how to move cars through drive-thru lanes more quickly and run their businesses with fewer employees.

“This is in response to more recent demands and trends,” said Keba Samuel, co-chair of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission, an advisory board. “My issue personally is that how do you settle the conflict between what our environmental and sustainability goals are with a request like that, and also some of the advances we want to see with regards to pedestrians?”

Chick-fil-A and Bojangles (which has already closed the Randolph Road location pending remodeling) didn’t respond to requests for comment about their restaurant plans. But the tension lies between future visions and present economic realities. While planners are promoting a new vision for Charlotte, built on density, walkability, multimodal transportation and better connections, market forces are often pushing the other way. In the case of fast food restaurants, dine-in sales have plummeted (down 32% year-over-year, per a recent study from Black Box Intelligence) and drive-thru business has surged (up 47%).

Restaurant operators expect the shift to be durable, which is why everyone from Bojangles and Chick-fil-A to McDonald’s and Taco Bell are expanding drive-thru-only designs.

And there’s another tension at work here: Planning for big changes and an aspirational tomorrow while managing today’s growth under current rules. The contentious 2040 plan debate this year focused on setting a high-level vision, but the actual rules of the road for builders are still a ways off. Charlotte plans to approve a new Unified Development Ordinance next summer, which will mark nearly a decade since the city started overhauling its outdated zoning and land use regulations.

What’s driving the drive-thrus

There are two simple reasons drive-thru only restaurants are spreading in Charlotte: People want to use them, and the pandemic forced businesses to make drive-thrus work better when dining rooms were closed. Chick-fil-A posted its best year ever for sales, with profits jumping 26%, despite closing dining rooms from March 2020 onward.

The economics for restaurant owners can be compelling. In 2018, during a public presentation on the Woodlawn Chick-fil-A’s rezoning request, a representative for the company said 83% of that location’s business already came from the drive-thru or take-away orders. Drive-thru-only restaurants need less space: Compare a rezoning request from Chick-fil-A on South Boulevard for a conventional store, with 5,000 square feet and 124 indoor seats, to the Woodlawn location, which is about 3,000 square feet with no indoor seating. The restaurants also need fewer workers, with no one cleaning tables and dividing their time between counter service, kitchen and the drive-thru. That’s a key consideration for restaurants at a time when wages are rising fast and it’s tough to find workers to fill the demanding jobs.

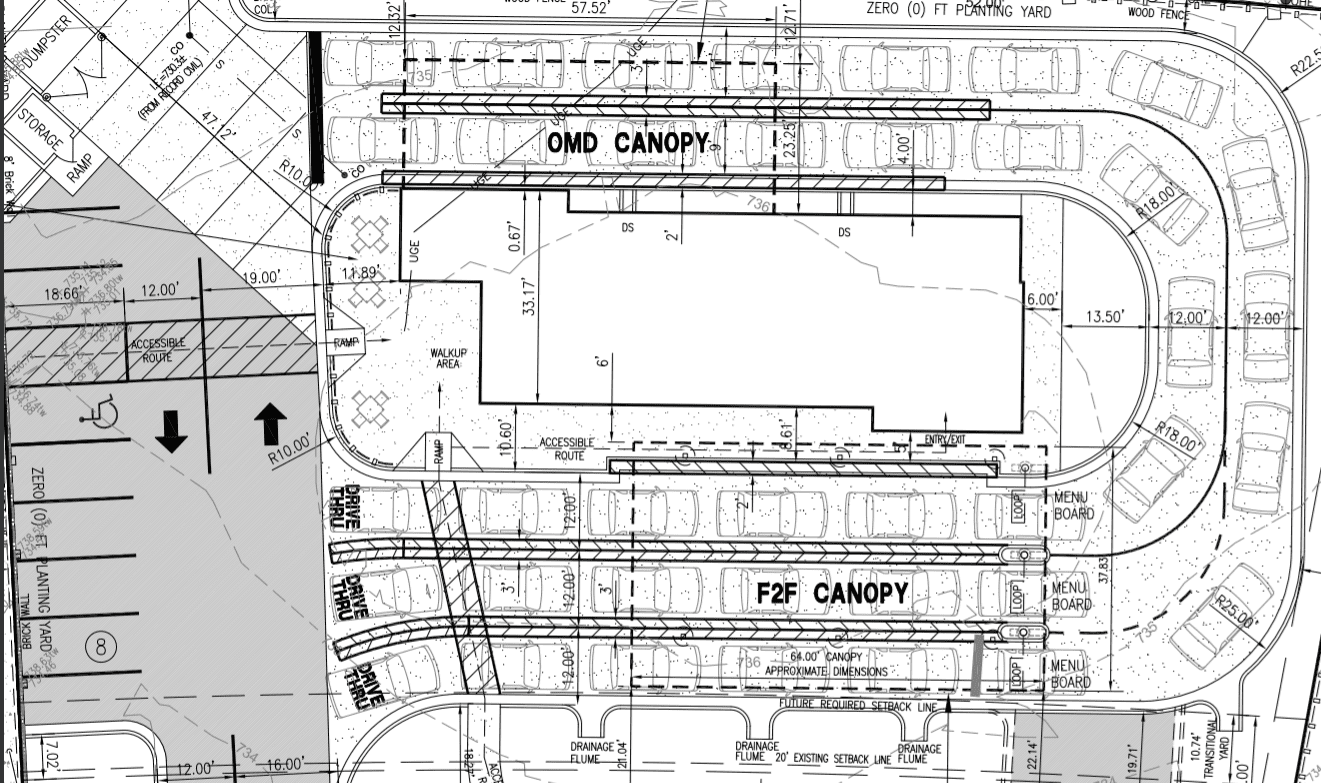

And yet, as much sense as drive-thru-only restaurants might make economically, they’re obviously at odds with creating a pedestrian-friendly landscape. While the Chick-fil-A at Randolph would have a walk-up window, site plans show the building set back from the street and cut off by a moat of cars. You’d have to cross either a two-way driveway or three lanes of drive-thru traffic to reach the walk-up window.

Site plan for the Randolph Road Chick-fil-A. Source: City of Charlotte rezoning filings

To be sure, the Randolph and Sharon Amity area as it stands now is far from a pedestrian-friendly paradise. It’s a stretch of busy, four-lane roads ringed by auto-centric uses like gas stations and oil-change shops, with narrow sidewalks frequently bisected by driveways, where drivers whip through turns and walkers step gingerly. Yet it’s also in the heart of a densifying part of Charlotte, with apartments, single-family homes and townhouses on all sides. From grocery stores to beauty salons, doctor’s offices to employment hubs like Sonic Automotive’s headquarters, every kind of commercial use is located right there.

If there’s an area that meets the city’s much-touted definition of a “10-minute neighborhood” — a place where people might be tempted to leave their cars and walk or bike, with the right infrastructure investments — this should be it.

Between the present and the future

Development obviously hasn’t hit pause to let Charlotte rewrite its development rules. That could lead to a mismatch between what’s built now and what the city aspires to in the future.

“Development has not stopped. If anything, it’s just accelerated,” said Samuel.

At Randolph and Sharon Amity, the city’s draft policy map shows the parcels with Bojangles and Chick-fil-A designated as “community activity centers.” That place type would translate into a zoning designation as “CAC-1” or “CAC-2” (yes, there will still be jargon in the new development ordinance), and, according to the descriptions of those districts, drive-thrus aren’t the goal there.

The Bojangles on Randolph Road. Photo: Ely Portillo

“The CAC-1 Community Activity Center 1 Zoning District is intended to accommodate those areas of the City that are transitioning from a more automobile-centric orientation toward a more walkable, well-connected, moderate intensity mix of retail, restaurant, entertainment, office, and personal service uses, including some residential uses,” the plan notes. And CAC-2 would require “a walkable and bikeable mixed-use development form” and “a comfortable pedestrian environment.”

Neither of those jibes with drive-thru only establishments, and the draft development regulations show drive-thru establishments wouldn’t be allowed in CAC-1 and CAC-2 districts (a drive-thru accessory could be permitted as a conditional use). The rules aren’t finalized, and individual parcels won’t be rezoned to conform to the new plan for a year or more, but the case of the Chick-fil-A and Bojangles shows how Charlotte could end up with developments that don’t match the city’s intended land uses (Like along the Blue Line, where large gas stations and auto dealerships dominate areas near the city’s light rail).

Samuel said drive-thru-only restaurants might make sense to mitigate traffic in places where it’s dangerously backed up at existing businesses. But she wishes developers would concentrate new ideas like indoor-seating-free restaurants in areas like South End where people might reach them by light rail, or walk up to a counter along a sidewalk and take the food to eat in a nearby park, rather than solely in their cars.

“I would wish they be a little more creative in thinking long-term with more flexibility,” she said.

In other neighborhoods that already have updated land use regulations, city planning staff are pushing back on car-centric plans. Staff have indicated that they’re not likely to recommend approval of Chick-fil-A’s expanded restaurant at South Boulevard and Carolina Pavilion Drive South. The reason: “The site is recommended for TOD (transit-oriented development) and a [restaurant] with a drive through with more parking than max in TOD is not consistent with the recommendation.”

That’s only possible because the city went ahead two years ago and rezoned nearly 1,800 acres near Blue Line stations to its new transit-oriented development districts. In the rest of the city — like at Randolph and Sharon Amity — the old rules still apply.

“It’s a challenging time. We’re in a transition period,” said Samuel.

In the end, more drive-thru-only establishments popping up across Charlotte might be an inevitable outcome of the economic forces pushing restaurant owners to cut costs and serve more people faster. Customers want to drive up, grab their food and drive away; after nearly two years of avoiding eating in a plastic booth around screaming kids, many of us have found we’re not actually eager to return. And a redesigned Chick-fil-A with three drive-thru lanes might solve the traffic backups that are a daily headache on Randolph Road.

But as city leaders talk ceaselessly about the need to move away from the car-centric, hostile-to-pedestrian development patterns that defined Charlotte’s growth for most of the post-war era, they’ll also confront this thorny question: Will we ever get out of our cars if we keep building more car-only businesses?