The forest unseen

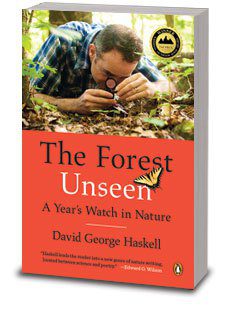

Is it possible “to see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wildflower” as poet William Blake suggested? According to biologist David George Haskell, this “search for the universal within the infinitesimally small” runs through many cultures. Tibetan monks create mandalas, paintings of sand that represent the entire universe within a circle about a meter in diameter. These inspired works of art prompted Haskell to ask, “Can the whole forest be seen through a small contemplative window of leaves, rocks and water?” Answers emerge in his book, The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature, a 2013 winner of the Reed Environmental Writing Award and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Haskell chooses a mandala-sized patch of old-growth forest on a slope of the Cumberland Plateau, a mountainside known as Shakerag Hollow because the thirsty townspeople of Sewanee, Tenn., once waved rags to summon the moonshiners at work on its flank. Haskell’s mandala is embedded in a dozen acres that somehow escaped the widespread timbering on these slopes a century ago. A professor at the University of the South, he resolves to visit the spot as often as possible over the course of a year.

Haskell chooses a mandala-sized patch of old-growth forest on a slope of the Cumberland Plateau, a mountainside known as Shakerag Hollow because the thirsty townspeople of Sewanee, Tenn., once waved rags to summon the moonshiners at work on its flank. Haskell’s mandala is embedded in a dozen acres that somehow escaped the widespread timbering on these slopes a century ago. A professor at the University of the South, he resolves to visit the spot as often as possible over the course of a year.

Haskell’s diligent observations, keen insights and academic explorations coalesce in a series of almost-weekly essays. Most months have three or four entries; fecund April earns seven. On New Year’s Day, he muses on the lichens adorning the rocks around him. “The quietude and outer simplicity of the lichens hides the complexity of their inner lives,” he writes. He goes on to describe this complexity, demonstrating a knack for making arcane scientific ideas and processes accessible to a lay audience.

To do this, Haskell often employs fresh and incisive metaphors. He compares moss bodies to “swampy river deltas miniaturized and turned vertical.” He also claims moss “carries a botanical camel’s hump as it trudges through long stretches of aridity.” The same delightful clarity is also bestowed upon the critters of the forest. “Salamanders are the sharks of the leaf litter, cruising the waters and devouring smaller invertebrate animals,” he writes. Given the multitude of slugs and snails inhabiting his mandala, he comes to think of it as “a molluskan Serengeti.”

Haskell’s book has convinced me I’m in desperate need of a hand lens. I’ve long considered binoculars an essential tool for wildlife observation, but I’ve obviously neglected far too many riveting dramas in the forest. This is an unfortunate pattern of behavior for me. I also remained oblivious to the series Breaking Bad during the first few years of its run. I was vaguely aware of its existence – and its purported magnificence – but it took me an inordinate amount of time to focus my attention. When I finally tuned in, I was instantly hooked. Thanks to Haskell’s essays, I now imagine viewing the tiny wonders of the natural world through a hand lens might become equally addictive.

If The Forest Unseen were made into a television series, it would likely be relegated to cable. There are the intimate details of plant and animal reproduction to consider, and then there’s the scene in which Haskell strips off his clothes on a blustery winter day in order to “experience the cold as the forest’s animals do.” His inspiration comes from a flock of Carolina chickadees that “dance through the trees like sparks from a fire.” Quickly bundling up again, he is humbled by the chickadees’ “insouciant mastery” of the frigid forest. They shiver to generate heat and loft their feathers to retain it. This is a simple and elegant solution, but it requires tremendous amounts of energy. Despite their acumen at foraging, the birds often struggle to find enough calories to sustain them through the night. “In the morning, the chickadee population in this forest will be better matched to winter’s demands,” Haskell somberly notes. His words are especially poignant in the wake of the polar vortex we experienced recently.

The structure of The Forest Unseen makes this a book to be revisited weekly over the course of a year. I plan to keep a copy on my bedside table or by my favorite reading chair. Haskell’s observations have opened my eyes to the abundance of life around us in the forests of the Uwharries. This is a singular book, one that deserves to be savored. Just as Haskell says of the chickadees’ ability to survive the cold, “Astonishment is the only proper response.”