The racial wealth gap: Business ownership & entrepreneurship

We recognize the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor are connected to the same systemic and institutional racism that created and sustains the racial wealth gap. We recognize that addressing racial violence and the racial wealth gap is dependent on systemic and structural solutions rather than the individual solutions that have placed the weight of societal change on the survivors of racial violence and inequity. The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute will continue work like the Racial Wealth Gap series with the guidance of our community and we commit to examine our role in the problem of racial inequity and our contribution to solutions.

This is the fifth in an ongoing series, based on a report by the Urban Institute. The report was compiled with support from Bank of America, which partners with the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and the Institute for Social Capital on research that provides insight into community initiatives. Join us Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. on Twitter for a discussion, using the hashtag #WealthGapWednesdays to follow along and ask questions.

Ninety-nine years ago this week, the Tulsa Massacre of 1921 destroyed 35 blocks of the Greenwood neighborhood, an affluent Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma, also referred to as a Black Wall Street. Estimates suggest between 100- 300 Black residents were murdered, 6000 were arrested, and over 150 Black-owned businesses were burned to the ground.

The massacre in Tulsa was preceded by the White looting and then destruction of Black family belongings, homes, and businesses — assets that had been built in the period following the Civil War. The massacre is just one example of the destruction of Black businesses and the violence that has historically accompanied the destruction. In addition to physical violence, urban renewal and the Federal Highway Act also destroyed Black and Brown businesses or separated them from their customers in neighborhoods like Brooklyn — Charlotte’s Black Wall Street — and Cherry.

[The Racial Wealth Gap in Charlotte-Mecklenburg: Read the new report]

Business ownership has historically been a strong wealth builder for communities of color. Nationally, the median net worth of Black and Latinx business owners is more than ten times that of their peers who don’t own a business.

In Mecklenburg County, business ownership rates are proportionate to the racial and ethnic makeup of the county. But disparities persist: Although ownership is demographically proportionate, the majority of the economic value of business ownership is held in a small number of White-owned businesses.

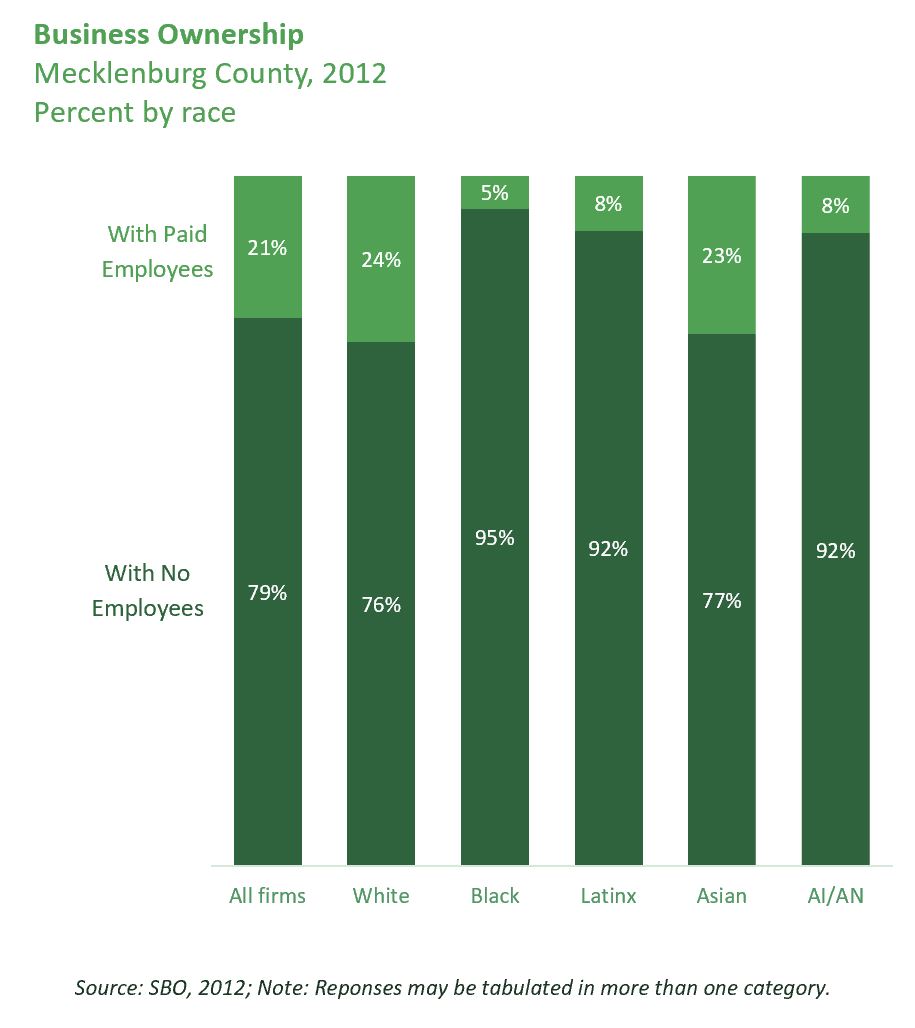

White-owned businesses are much more likely to have businesses with paid employees. About one-quarter of White-owned businesses have employees (other than the owner), compared to less than 10% of businesses owned by Black or Latinx individuals in Mecklenburg County, according to the most recent data from the Survey of Business Owners (SBO).

Here’s why that’s important: The number of employees in a business increases overall success; businesses with employees have much higher sales than businesses without employees.

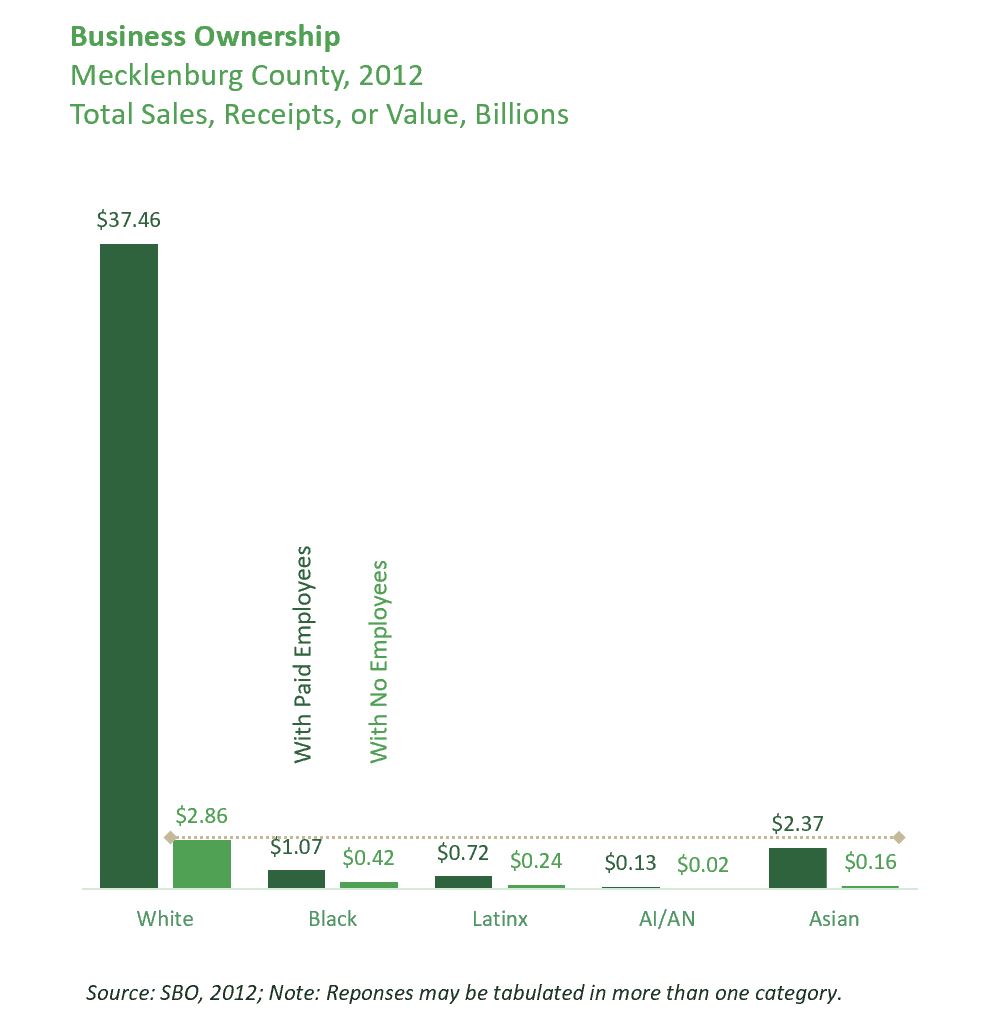

In Mecklenburg County, the 24% of White-owned businesses with employees account for vastly more money in sales, receipts, and value than any other group. According to a UNCC Urban Institute calculation of data from the most recent SBO, White-owned businesses total $35 billion more in sales, receipts and value when compared to any other group of businesses.

Business ownership is one pathway to accumulating wealth, but owning a business is more likely to be a significant part of wealth for White and Asian households- business and financial assets make up a third of their overall assets. For Latinx households, that number falls to 15 percent of total assets, while business and financial assets make up just 8 percent of Black households’ total assets. This indicates that on average White- and Asian-owned businesses are much more profitable than Black-and Latinx-owned businesses. The presence of the racial wealth gap means that businesses owned by people of color have less up-front, personal capital to start and maintain a business.

The Racial Wealth Gap

- Part 1: COVID-19 exposes the impact of the racial wealth gap

- Part 2: The historical roots of the racial wealth gap in Charlotte

- Part 3: Home ownership and the legacy of redlining: Charlotte’s racial wealth gap

- Part 4: How income and industry contribute to the racial wealth gap

Similar to income, industry-type plays a role in the success and profitability of small businesses. Small businesses in industries like technology, healthcare, and professional services tend to be more profitable and also boost the success of businesses that operate in the same community. These industries, however, are typically underrepresented in majority Black and Latinx communities, while industries with generally lower profit margins and cash liquidity — such as repair, maintenance, and restaurants — make up a larger share of small businesses in communities of color.

Additionally, home value and education level, both pathways to wealth accumulation, seem to be an indicator of profitable businesses. A report by JPMorgan Chase found that small businesses in communities with high home values have about twice the profit margins of businesses in communities with low home values. Small businesses in communities with a higher number of college graduates had 10% higher profit margins than businesses in communities with fewer college graduates.

Small business success in areas with greater home values and higher levels of education, both their own pathways to wealth accumulation, speaks to the multifaceted and cumulative nature of wealth and the racial wealth gap.

Even when small businesses owned by people of color have thrived, our policies and practices have routinely stripped away these opportunities for wealth. “Black Wall Streets” and other corridors with a high concentration of successful businesses, especially Black-owned businesses like Brooklyn in Charlotte, have historically been targeted for redevelopment through federal programs like urban renewal or the Federal Highway Act. Other acts, like the Tulsa massacre in 1921 or the Wilmington massacre in 1898 have been more overtly violent. The Wilmington Massacre, also recognized as a coup d’etat of a democratically elected government, killed between 60- 300 Black people and destroyed Black businesses.

These practices eliminated wealth building opportunities for these Black-owned business clusters and the potential to pass that wealth to future generations.

Barber James Daughtry shows off his high school yearbook.He keeps it on hand to share with customers at Charles & Son Barber shop. His employer, Charles Alexander, has operated this barber shop on Statesville Road for decades. Photo: Nancy Pierce

COVID-19 puts small businesses at risk

Federal support for small businesses dried up on April 16, just two weeks after the funds became available. Although more support is likely coming, the administration of the funds has seen immense challenges, with funds going to large companies, instead of small businesses. The program structure places immense priority on businesses with a large number of employees with the potential to garner higher fees. This makes it especially difficult for the more than 90% of Black- and Latinx-owned businesses without employees to qualify for assistance.

As of May 25th, the number of active small business owners fell more than 20% nationally since the start of the pandemic. For Black-owned businesses the number is double that, with COVID-19 related closures decreasing the number of working Black small business owners by more than 40%. Working Latinx business owners dropped by 32% and Asian business owners fell by nearly a quarter. Additionally, immigrant business owners decreased by more than a third.

Furthermore, businesses in Black and Latinx communities have less than three weeks of “buffer cash” to continue operations in economic downfalls such as the one induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. This means that these businesses are much less likely to reopen without the necessary assistance.

The impacts of COVID-19 have put small businesses owners of color on shaky ground and the racial and ethnic disparities in small business profits are likely to grow. Solutions are rooted both within and outside of our COVID-19 response. Several promising solutions, such as employee ownership conversions are growing practices.

Business ownership and entrepreneurship policy solutions

Addressing inequality in business ownership, and ultimately the racial wealth gap stemming from these inequalities, depends on solutions that focus on fixing systems, not people. Proposals include using a targeted approach, setting goals that benefit all and then targeting strategies in order to ensure that goals are met for historically marginalized groups. Combining solutions within and across systems, and focusing on solutions that can stretch across generations are also critical frameworks to meaningfully address the racial wealth gap.

The solutions outlined below include policy changes and evidence-informed practices from subject matter experts that bridge racial and ethnic gaps in business ownership and entrepreneurship, components of the racial wealth gap.

Reparations: Economically redress the free labor of slavery and subsequent White acts of violence that have resulted in the loss of life, income, businesses, and wealth among descendents of slaves and massacre victims.

-

Ta-Nehisi Coates: The Case for Reparations

-

Patricia Cohen: What Reparations for Slavery might look like in 2019

Darrick Hamilton and Trevon Logan: Here’s Why Black Families have Struggled for Decades to Gain Wealth

Minority Business Capitalization and Support: Strengthen policies and programs that invest in developing, sustaining, and growing minority-owned businesses, including expanded access to capital through loans, grants and venture capital, and support for alternative community business structures like neighborhood cooperatives.

Employee Ownership Conversion: Employee Ownership Conversions are business ownership transitions that allow employees to build assets, maintain income, and prevent the closure of local businesses when owners retire. There are two types of conversions. Worker-Owned Cooperatives are business entities in which ownership and management is shared among some or all of the employees of a company. An Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) is a benefit plan that allows employees to acquire ownership stakes in their company.