Social Capital: A Tale of Caution and a Tale of Hope for Charlotte

This article was written by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute. Data utilized in this series was collected in partnership with Leading on Opportunity, Opportunity Insights, Communities In Schools, YMCA of Greater Charlotte, Foundation For The Carolinas and SHARE Charlotte, and with staff funding from The Gambrell Foundation. To see more results from the 2019 Mecklenburg Social Capital Survey, visit our Social Capital Reports page.

Fifty out of fifty. It’s a phrase that has become familiar in Charlotte conversations over the last six years. The phrase calls the Charlotte area out as having the lowest economic mobility rate of any major city in the U.S. Only about 5% of children born in Charlotte to a family in the bottom fifth for income are expected to make it to the top income quintile as adults.

Raj Chetty — the primary author of the now-famous economic mobility study — and his colleagues found five factors that contributed to Charlotte placing last in economic mobility: residential segregation, income inequality, poor primary schools, family instability, and lack of social capital. Of these factors, social capital is the most difficult to understand, yet the Leading on Opportunity Task Force noted it as possibly the “secret sauce” that could lead to greater economic opportunity in our region.

[More detail: Social capital in Mecklenburg County]

This article series will examine social capital in Charlotte-Mecklenburg using observational results from UNC Charlotte Urban Institute’s 2019 Social Capital Survey. These articles will help to answer questions such as: Who trusts their neighbors? Who trusts the police? Where do people turn to for support and connections? But first, what is social capital, and why do we care?

Social Capital: What is it and why do we care?

Social capital most simply refers to the material resources or non-material benefits arising from our social relationships and networks. Academics and social commentators have debated the nature and impact of social capital for decades, generally drawing from three theoretical traditions.

Chetty and colleagues measure social capital using Robert Putnam’s social capital indices. Putnam, who popularized the term, viewed social capital as the aggregate amount of trust among people and institutions that lead to cooperation and resulting benefits. Putnam drew from the work of fellow sociologist James Coleman who also defined social capital as a collective asset and suggested that greater social capital could offset a lack of available human and cultural capital. In contrast to both Putnam and Coleman, sociologist Pierre Bordieu described social capital in terms of power and its ability to reproduce economic inequality through social and institutional relationships.

It matters how communities understand social capital and use it to address problems. Some argue that social capital is the foundation for collaboration between neighbors and communities, a safety net during hard times, and can be a ladder to upward economic mobility. However, others have cautioned that social capital can be used to label those who don’t have access to resources through their social networks or used to reinforce economic inequities.

Considering this complexity, this article looks at two perspectives on the social capital narrative- a cautionary tale and a case for economic mobility. In doing so, we conclude that an equity-focused approach is essential if social capital is to truly improve economic mobility for economically disadvantaged Charlotte residents.

The Dark Side of Social Capital

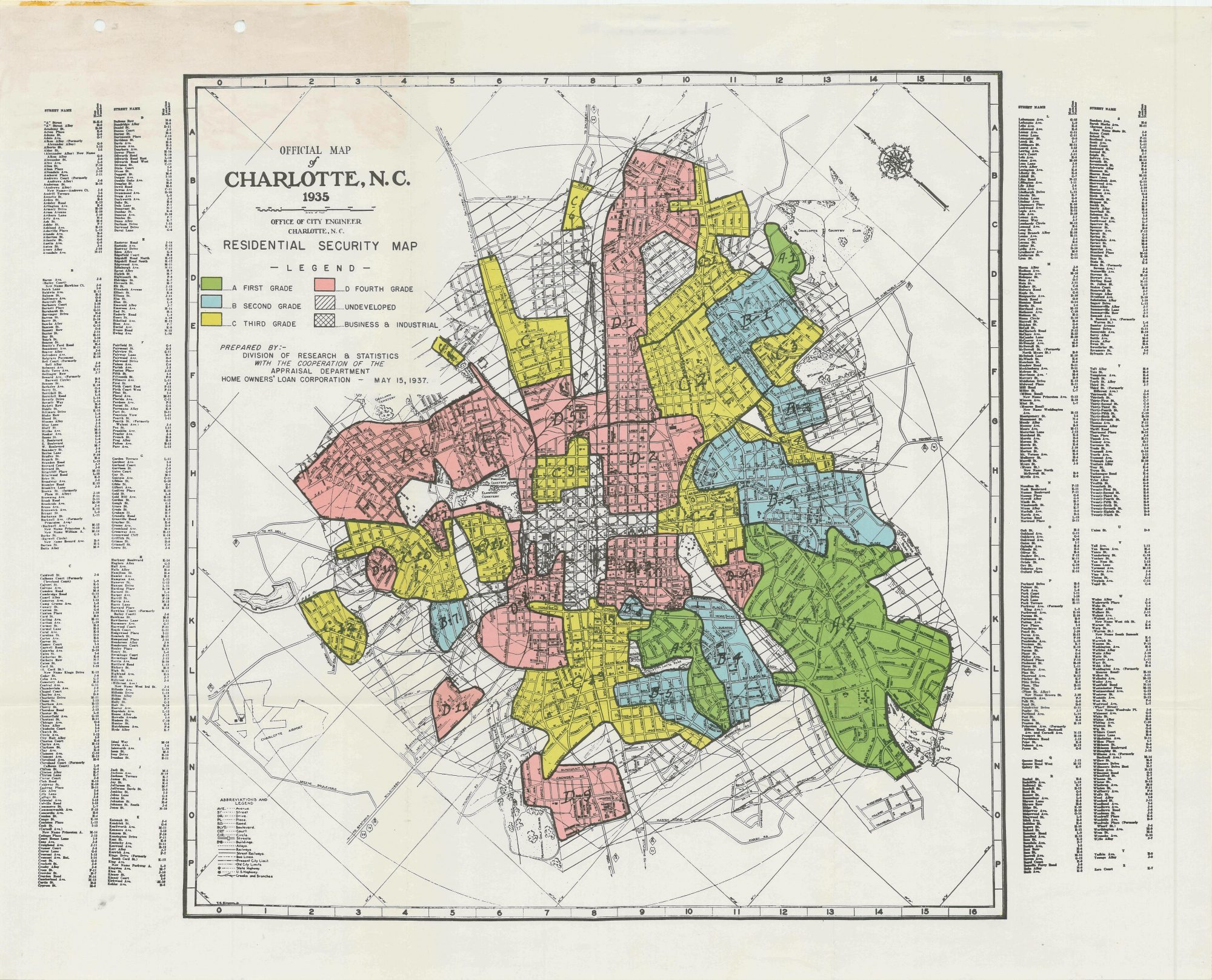

One of the major critiques of social capital is that it can be used to produce or perpetuate inequalities by providing opportunities to a select group at the expense of others . Historic and current discriminatory public policies and practices in housing, education, banking, and criminal justice have systematically excluded people of color from receiving the same economic opportunities as their White counterparts (see Racial Wealth Gap series for more). These policies have shaped Charlotteans’ social capital by influencing where we grow up, who we go to school with, and how much we feel like we are included and valued by our community institutions.

For example, if I were born to a wealthy family and raised in one of south Charlotte’s wealthy neighborhoods, from a young age I would be surrounded by a network of financially successful people who teach me about their careers and connect me with internships. Since my family can afford it, I attend an elite private school and then college where I am exposed to new networks, resources, and connections that further expand my social capital. I am likely White and have never worried about how the color of my skin may bias a potential employer, the police, or mortgage lender against me.

If I were born to an economically disadvantaged family in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood in Charlotte, I am unlikely to have the same access to networks of financially successful people as my wealthy counterpart. This is not to say that I don’t benefit from rich relationships that help me on my educational or career journey. If I am Black or Latinx, I may have experienced discrimination or exclusion that make it more difficult for me to feel a sense of belonging or trust in institutions who have treated me unfairly.

This dark side of social capital tells us that left on its own, social capital has the power to reproduce and expand the inequities already present in Charlotte. It also cautions us against focusing exclusively on individual-level solutions without addressing the systemic problems and structural relationships that lie at the root of the problem.

An equity-focused approach is essential if social capital is to truly improve economic mobility for economically disadvantaged Charlotte residents.

The Hope of Social Capital

Social capital has the power to reproduce inequality, but it doesn’t have to be that way. The economic mobility study offered some of the first empirical evidence that higher social capital is directly linked to economic mobility. The lingering question is: how do we ensure that strategic efforts to increase social capital promote equity and address historic and systematic barriers to accessing social capital?

Organizations such as Communities In Schools and the YMCA of Greater Charlotte have designed initiatives to address this question.

Communities In Schools launched The Social Capital Initiative in 2019, which connects high schoolers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds with local job shadowing opportunities, informational interviewing, college scholarship opportunities, resume writing workshops, and other college and career readiness skills. Communities In Schools also piloted similar social capital offerings to middle school students as well. Prior to attending any social capital exchange, students learn about the historical barriers to economic mobility in Charlotte and how social capital is connected with opportunity.

The YMCA of Greater Charlotte offers a variety of social capital-building programs, such as Y Readers and Y Achievers, which promote academic achievement and mentorship for students. The YMCA has also worked with the community to launch My Brother’s Keeper Charlotte-Mecklenburg or MBKCLTMeck, a backbone organization committed to driving positive outcomes for Boys and Young Men of Color. MBKCLTMeck is the registered MBK Network of the Obama Foundations MBK Alliance. Many other organizations around the city are also incorporating social-capital building strategies in their work.

Measuring Progress toward Social Capital Equity

To date, most social capital research has focused on where social capital is occurring naturally in a community. Researchers have studied voting behaviors and organizational memberships. They have surveyed community members about how much they trust their neighbors or who they turn to for support. This observational research helps us understand the state of social capital in our community.

Little published research has measured the impact of social capital interventions on economic mobility. This means that while we know that there is some kind of correlation between social capital and economic mobility, we are just beginning the process of understanding which programs, policies, and structural changes actually improve social capital and lead to economic mobility.

This article series will examine social capital in Charlotte-Mecklenburg using observational results from UNC Charlotte Urban Institute’s 2019 Social Capital Survey. These articles will help to answer questions such as: Who trusts their neighbors? Who trusts the police? Where do people turn to for support and connections?

These results can serve as a baseline for social capital in our community in order to measure our progress towards improving access to economic mobility for those who are traditionally excluded.