Is there a leadership deficit in rural communities and small towns?

“The more successful towns have a champion. The really successful ones have multiple champions.”

We visited Liz Parham, director of North Carolina’s Main Street Program, to learn about how communities across the state are capitalizing on their cultural and natural assets to revitalize local economies.

But it was a different type of asset – people and the leadership they can bring to civic affairs – that she regularly highlighted as one of the greatest predictors of community success. Parham summarized a common theme we heard throughout our research for the Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection project: the importance of leadership in determining the economic success of small towns and rural communities.

No matter where we went or who we talked to, the question of leadership surfaced. In successful communities, as Parham noted in her comment about “champions,” people pointed to individuals who had the skills to mobilize their community around a shared vision, and the tenacity to stick with that vision over time when the inevitable setbacks emerged.

[Read more: What’s being done to bridge understanding between urban and rural leaders?]

As former Salisbury Mayor Margaret Kluttz said about her community’s success using historic preservation as a catalyst for downtown revitalization, “it took us twenty years to become an overnight success.”

What happens, however, if a community doesn’t have champions to lead it forward? And do our rural communities have such champions – or are they losing their leaders?

| The Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection A special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

| Read about the project here |

| Introduction: Strengthening ties to revitalize communities |

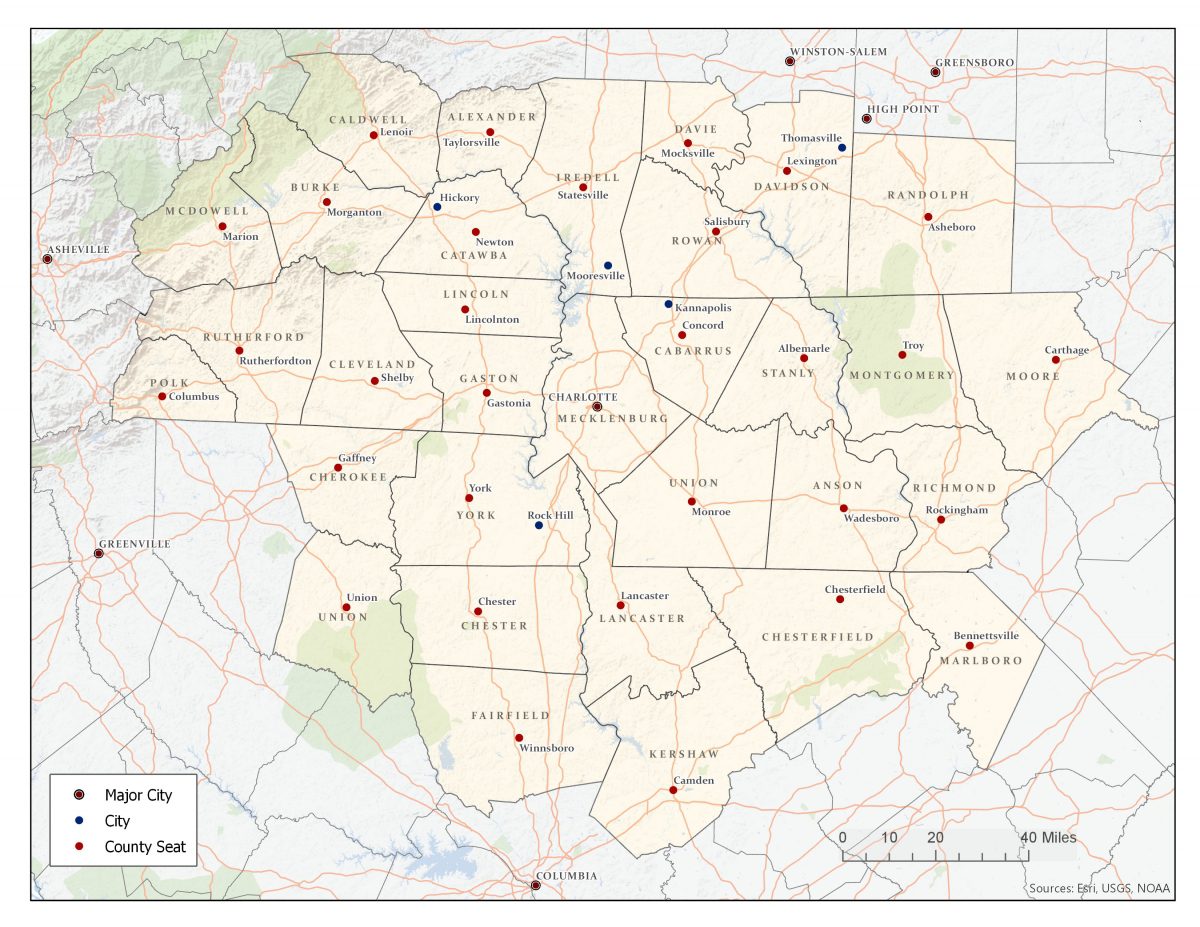

| Defining our study area: How we picked the 32 counties |

| Historical Overview Part 1: The early development of a connected region in the Carolinas Piedmont |

This is not the first time we at the institute have heard about the importance of leadership to the Charlotte region’s long-term success. Nearly 25 years ago, the institute and a coalition of regional newspapers led by the Charlotte Observer invited national urban writers Neal Peirce and Curtis Johnson to assess the challenges facing the Charlotte region as the dawn of the 21st century approached.

In a special series called “The Peirce Report,” they argued for a more inclusive approach to decision-making, calling the Charlotte region “a place where people perennially assume a powerful bunch of bank presidents and other men (always men) call the shots.”

But something seemed different about the way people talked about leadership during our interviews for the Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection project. Peirce and Johnson focused more on inclusion, and how new voices (primarily in the urban and suburban core) were demanding a seat at the table. The concern we heard now in the smaller towns and communities of the Charlotte region was different: are there still people willing to step up to the table at all, or is there actually a growing “leadership deficit” in some places?

Changing towns and businesses

That anxiety appeared to be driven by several factors: the loss of young people departing their hometowns to find better jobs elsewhere; the rise of dual-income families, leaving little time for either parent to be engaged in civic affairs; and the loss of homegrown businesses and establishments such as textile mills, banks and hospitals, eliminating the talent pool from which many nonprofits traditionally drew their board members and volunteers.

Even if the local bank or hospital still exists under a different name and outside ownership, many people we interviewed perceived that managers weren’t likely to remain in the community as they moved up the corporate ladder. They felt smaller towns have become the farm leagues of corporate America, where mid-level managers are groomed before being called up to the majors in bigger cities. Those who expressed this concern felt that transient management had reduced the possibility of leaders from the corporate sector ever developing the deep understanding of a place that translates into effective civic engagement.

Patrice Roesler, who works with community leaders throughout North Carolina as part of the UNC School of Government’s Center for Public Leadership and Governance, sees it as part of the broader “societal mobility” that affects all of America, urban and rural alike.

But she feels small towns and rural communities are especially vulnerable because of the importance people place on relationships of trust and understanding, and she worries managers who don’t stay long-term won’t “have the heritage that locals trust.”

We heard a new term – the “reverse commute” – to describe a growing phenomenon in many towns and communities 40 to 60 miles outside of Charlotte. The professional class (doctors, bank executives, and even municipal government administrators) are choosing to live in Charlotte’s nearby suburbs to be closer to the amenities of the urban core, while commuting “out” to work in places like Albemarle, Salisbury and Lancaster. Not only does the longer commute leave little time for civic engagement, but there is no longer the same emotional investment that comes from living and raising a family in the same place where one works.

.

.

More ‘visceral and organic’ leadership?

At least, that’s some of what we heard in our interviews. While not discounting legitimate concerns about the impacts of demographic change and economic restructuring on the leadership of rural communities, we couldn’t help but take note of the evidence of successful leadership throughout the region, and the near-universal persistence of civic pride in every community we visited. So, we reached out to several individuals who are in the business of leadership development, especially those working in rural communities, to get their take on the “leadership deficit” question.

While most agreed that there are indeed leadership challenges facing rural communities, no one would go as far as calling it a leadership deficit or even crisis. Instead, most described what is happening in rural communities as a period of transition that is disorienting for many accustomed to the traditional leadership paradigm of old families and business leaders making all the decisions.

According to Kathleen Marks, NC Director of The Conservation Fund’s Resourceful Communities program, “there is a lot of grief in rural communities about the loss of the earlier way of life.” That extends to leadership, where many grew comfortable with the more paternalistic style of the past.

Marks feels that traditional style is now giving way to a more “visceral and organic” type of leadership, and that there “may actually be a higher percentage of the population in rural communities involved in leadership roles today than ever.”

Cyndee Patterson, president of the Charlotte-based Lee Institute, which runs a regional chapter of the national American Leadership Forum, agrees.

“There are leaders, but they are often different from the past, including more women and people of color,” she said. ”There’s also a phenomenon of people who grew up in these communities and have been away for many years, who are now moving back and assuming positions of leadership.”

Patterson’s colleague, director Chrystal Joy, adds that “the models and paradigms of leadership are shifting.”

As Kluttz, the former Salisbury mayor, noted when it comes to leadership outside of the state’s urban centers and their suburban satellites, “everybody is at a turning point.”

[Read more: What’s being done to bridge understanding between urban and rural leaders?]