Vision of Paris future evokes Charlotte’s past

PARIS – I saw the future in Paris. It looks a lot like the past. To be specific, it looks like uptown Charlotte circa 1989, but with flashier architecture.

While in the French capital earlier this year for a conference of urban planners and scholars, we toured La Défense, the huge development just west of the Seine. Half a century ago it was envisioned as the future of Paris, a district of towering offices and wide concrete plazas. Today it’s an office park whose huge cube monument doesn’t make up for its being dead at night.

“They were probably trying to imitate America,” concluded Georges Prevelakis, an urban planner and Sorbonne professor who was also at the International Urban Fellows conference of Johns Hopkins University’s Institute for Policy Studies. “This is completely outdated.”

In other words, La Défense is badly in need of the retrofit it’s undergoing.

Here in Charlotte, we understand the problems of a downtown that’s a glorified office park. Our uptown, like many, struggled for decades to add housing, nightspots and – well, life – on nights and weekends after the office workers drove home.

Not coincidentally, for years uptown Charlotte’s vision sprang from a 1966 vision by a Modernist architect of tall offices, wide streets and wind-swept concrete plazas. In other words, it looked a lot like La Défense.

As uptown Charlotte sprouted bigger and bigger office buildings, they needed bigger and bigger parking lots. Smaller, older buildings – the kind that give texture and life to a city – were demolished, usually for parking lots. Meantime, the vast U.S. suburbanization trends were buffeting Charlotte, with people moving to outlying subdivisions; stores, restaurants and nightspots followed them. By 1994, when the city hosted the NCAA Final Four basketball tournament, uptown was so dead at night that a series of faux nightspots were temporarily created in vacant buildings (now demolished, of course).

Eventually – with 1994’s fake nightclubs helping spark a realization that people would, in fact, go uptown for entertainment – the bankers and developers began building housing and retail spaces as well as offices.

In the United States, when we envision places with admirable urbanism, Paris is always near the top of the list with its gracious boulevards, plentiful parks and myriad of just-steps-away delis, cafes, butchers, boutiques and bakeries. Despite that excellent example in front of their noses, the mid-century French planners and developers instead ended up replicating the very things that were killing American downtowns.

The first part of La Défense opened in 1958. Today it’s a cluster of office towers with a huge treeless concrete plaza that rises up to an immense cube-shaped monument. In concept and architecture it reflects much of what went wrong with city-building in the last third of the 20th century. Despite the famous architects, virtually no attention was paid to the spaces between the buildings.

Nor, apparently, did they study the natural surroundings or they might have realized that the hill atop which they built – home to an 1883 monument named La Défense de Paris – is naturally windy. So when La Grande Arche opened in 1989 those winds, aided by skyscraper-induced wind tunnels, were so intense it was all but impossible to stand inside the cube. Today the stark design has been softened by a canvas canopy and glass panels somewhat reminiscent of a funhouse hall of mirrors – all installed as windbreaks.

It’s not that La Défense is 100 percent horrible. With some 150,000 daily workers, (but only 20,000 residents) the big plazas were filled with people during the lunch hour of a warm, sunlit weekday. Some of the planning was smart, too. With high demand for Paris development, building outside the older city was inevitable, although I wondered why they didn’t build more housing, as prices in central Paris are astronomical. Much of La Défense is built atop parking lots and highways, with transit stations (commuter rail and subway) below. In the newer section at the western end, more housing is being built, and buildings are being reoriented toward nicely landscaped terraces atop the transportation infrastructure. And I was cheered to see that in many office towers, the windows actually opened – a humane amenity by no means common in the U.S.

I asked our tour guide about some simple retail necessities: Pharmacy? It’s in a shopping mall hidden below the main level of the development. Bakery? Also below the surface. Restaurants? Most close by 9. No butcher. No charcuterie.

“I’m amazed to see a development like this in a city known for outstanding planning and design,” said Sandra Newman, a professor of policy studies at Johns Hopkins University who directs the International Urban Fellows program. “What were they thinking?”

In the end, the whole idea of La Défense is a monument to the power of faddish imitation by architects and planners – to the tendency to be suckered by size and to embrace important-sounding theories about how cities should work,  along with a willful suspension of belief in any visible evidence of how cities really do work. It wasn’t just the French embracing those fads; that’s one reason La Défense resembles so many American office parks-masquerading-as-downtowns.

along with a willful suspension of belief in any visible evidence of how cities really do work. It wasn’t just the French embracing those fads; that’s one reason La Défense resembles so many American office parks-masquerading-as-downtowns.

These days a huge retrofit project launched in 2006 is adding residences and retail spaces to La Défense. It’s also building yet more office towers by star-chitects such as Sir Norman Foster.

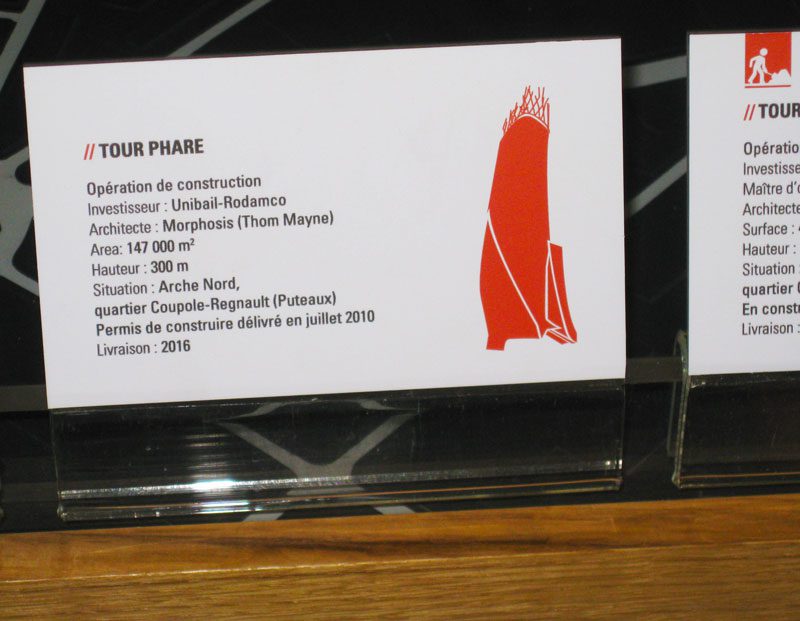

As we looked over a scale model, our guide pointed to an existing building next to a planned tower and said, off-hand, “Of course, this building will lose all its light.” Another tower, from Morphosis, looks strikingly like a huge, bent penis – not a design likely to be mimicked in America, and for once I am grateful for this country’s prudishness.

Has the French government finally learned that looking to America may not produce the best ideas for building and sustaining cities? The evidence is not cheering. Like so many U.S. cities, including Charlotte, plans for enlivening La Défense are based on – wait for it – a new sports arena.

This is France, not Charlotte, so it won’t be a ballpark, NBA arena or NFL stadium. It will be a rugby arena. Somehow, that does not make me feel much better.

Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.